Project Management

- Gain an understanding of what it might mean to work in project management.

- Reflect on the similarities and differences between project management and research.

- Explore the benefits of working within a project management framework.

Project management skills

Project management skills and an awareness of project management principles and methodologies are increasingly important in a wide variety of sectors and roles both within and beyond academia.

Project management is all about managing resources (time, money, people) effectively in order to meet defined goals. There are various methodologies and approaches to doing this, but at its heart, project management is about doing something new and working within a framework which increases your chances of success. The framework typically involves key activities such as: defining your goals, effective planning, monitoring progress, managing risk and engaging stakeholders effectively.

As you can see, many of these activities will already be familiar to you from your research career to date. It is very likely that you have developed skills relevant to project management already in your work as a postdoc. For example, many research grants require some level of project management – perhaps you have developed a project plan for a grant application or had to monitor progress against key milestones in order to report to a funder. Similarly, activities such as arranging conferences, symposia and public engagement events would benefit from a project management approach. Maybe you have learned this the hard way!

The purpose of this section is not to give an exhaustive overview of project management skills and methodologies. If you are interested in learning more about this, the professional body Association of Project Managers (APM) is a good place to start. Their website offers freely available resources regarding the nature of projects and the key skills and competencies required to manage them effectively.

Prosper's employer stakeholders

Throughout this section, you will find video and written content co-produced from activities with employer stakeholders. All work in project management in different contexts and their perspectives should give you an insight into the range of activities and sectors where project management is important. Our key stakeholders are:

- Chris Humphrey, Change Delivery Manager at Triodos Bank UK

- Rebecca Douglas, Group Programme Director, Talent at IPG Health Medical Communications

- Matina Tsalavouta, Head of Strategic Planning and Engagement at the Liverpool Cancer Research Institute

- Martin Squires, Senior Solutions Consultant at Merkle EMEA

What is project management and why it matters

‘Projects occur when an organisation wants to deliver a solution to set requirements within an agreed budget and timeframe.’

APM

A project is an endeavour that aims to deliver some value within the context of limited time and money.

Another way of thinking about projects is that they contrast with ‘business as usual’. Whereas a project is about doing something new (such as introducing a new service, designing a new product, perhaps even testing a new hypothesis), business as usual comprises the activities that form part of your everyday work and are not time limited.

Historically, ‘business as usual’ formed the majority of an organisation’s activity and project management was a nice endeavour. It is now standard practice and approach across many sectors.

“Previously, most of what an organisation did could be read from a handbook or from a process and there was a smaller part of the organisation that tried to do projects or prepare organisations for change.”

Chris Humphrey, Triodos Bank

“Project Management is effectively business as usual. Pulling a cross functional team to deliver an output for stakeholders has become 80% of a team’s deliverables [in data science].”

Martin Squires, Merkle

Projects are also important in organisations that operate as agencies, as the nature of these business is providing a set deliverable for a client, to a deadline and within a set budget.

“Project management is really integrated into everything we do. It’s critical to ensure we are meeting the client’s requests within the budget and the timeline that we’ve got.”

Rebecca Douglas, IPG Health

This is also the case within the third sector. While charities do receive ‘core’ funding grants to cover ongoing operational costs, they are much more commonly funded to deliver specific projects and outcomes.

A key reason for the ubiquity of project management across sectors is that the rate of change today is much greater than it was several decades ago. Not only is project management used much more broadly, but the nature and methods of project management have developed too, in order to respond to this change.

We look at this in more detail in the section on Agile Project management but more recently developed project management approaches reflect a commitment to flexibility rather than a pre-defined end point. Agile projects are more iterative in nature and in this way might be compared to experimental research.

“You have a hypothesis, a question, you design an experiment, you do your experiment, you get your results, you look at it and then you refine your methodological approach to progress with your research question. Recognition and acknowledgement of doing this while you are doing it, naming it as part of an agile way of working helps build your skillset [when considering] a different role where project management may be the essence of the professional work.”

Matina Tsalavouta, University of Liverpool

Research and project management

Research and project management

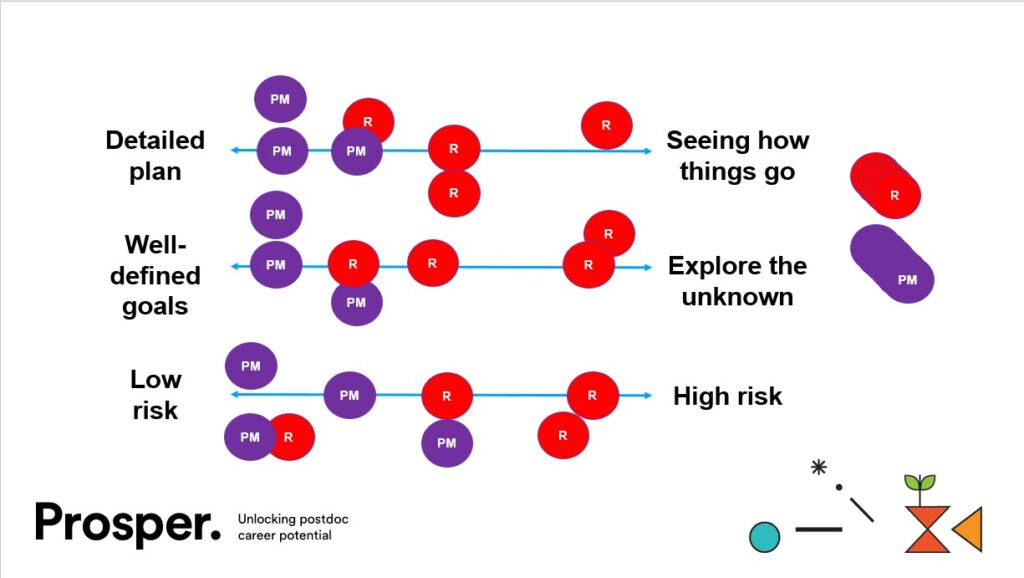

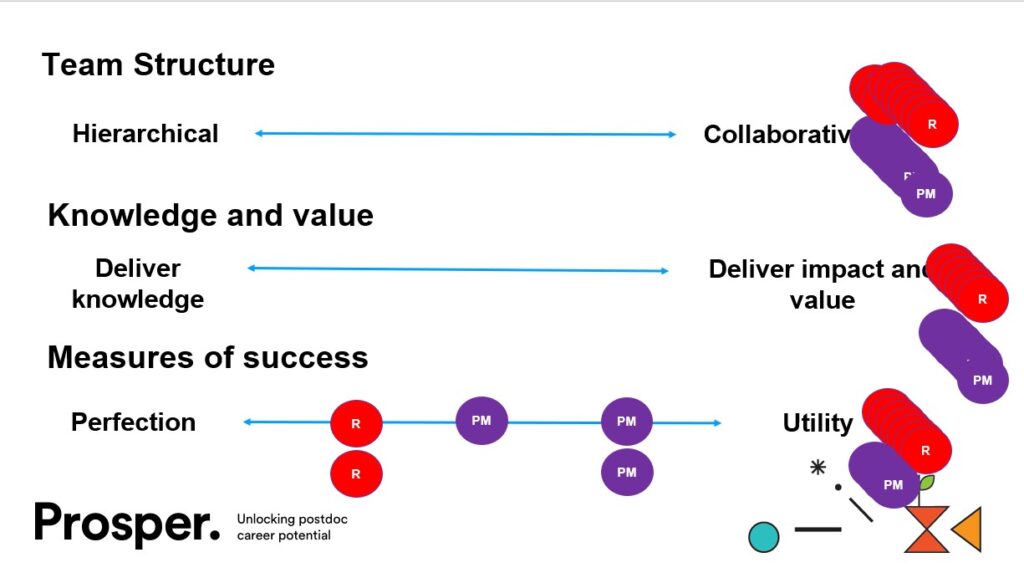

Here we compare research and project management across several different parameters. Let’s start with a quick exercise. Given your existing knowledge of research and any knowledge you have of project management, at which point along each of the following continua would you place research (R) and project management (PM)?:

Detailed Plan <-----> Seeing how things go

Well-defined goals <-----> Exploring the unknown

Low risk tolerance <-----> High risk tolerance

Hierarchical structure <-----> Matrix structure

Delivering new knowledge <-----> Delivering impact and value

Perfection <-----> Utility

Now, compare this with the responses of our postdoc workshop participants, here

TASK: Having completed this section and reflected on the responses of fellow postdocs and project management professionals, note down what, if anything, has changed regarding your view of the relationship between research and project management.

Risk and risk tolerance

Risk tolerance is a key point of difference when comparing project management and research. Active management of risk is an important part of project management and is not as prevalent in research projects (though large-scale grants increasingly require it).

Risk management typically involves:

- identifying and classifying all possible risks to project success in a document called a risk register

- rating the likelihood of each risk being realised and the potential impact should it be realised (typically from 1-5)

- classifying the level of risk based on this assessment, typically as high, medium and low.

- assigning appropriate resource to mitigate risks

- reviewing risk at regular intervals

While you may have done some or even all these things within your postdoc career, you may not have done so formally or considered them in such a formalised way.

Risk tolerance varies by project. In projects related to compliance or in heavily regulated sectors such as financial services, risk tolerance tends to be very low as the potential damage of not getting things right is high. When the stakes are lower, risk management can be lighter touch.

Risk tolerance in research also varies by the nature of the research: in highly regulated areas such as clinical trials, risk tolerance is similarly low. Other areas tend to tolerate more risk and, the increasing recognition of the value of negative results also reduces the perceived risk of research: even if the original hypothesis in not proved, there is still a contribution to knowledge that is beneficial.

If you’re interested in learning more about risk management, we’ve provided a short video outlining what it entails in the risk section of our Commercial Awareness resource.

Suggested task

Login or register to add these tasks to your personal development plan.

Video resources

Our employer stakeholders introduce themselves and outline their experience and background below.

So as I say, a warm welcome to the session. For those of you who don’t know me, my name is Katie McAllister and I, along with Chantelle am one of the stakeholder engagement managers on the Prosper Project. We’re really happy to have this session today on project management. I’ve got a great panel and I know lots of you have taken the time to complete the pre-work and give some thought to the session in advance. So we’re hopeful it’ll be a really good session. Before I invite the panel to introduce themselves, just a quick overview of the aims and the structure of the session this morning. So as you all know from the event, the purpose really is for us to explore some of the key principles of project management to convey and work out together why it matters in the broader employment landscape, as well as within the research environment. We’ll then do a little workshop, interactive session, looking at the pre-work that some of you have done, and doing a bit of a compare and contrast between research and project management, which we hope will be illuminating in getting you to understand more about project management, but also to perhaps uncover where you’ve used project management skills or worked within project management frameworks already as part of your research career. Then finally we’ll look a little bit at the Agile method in particular and explore how working within an Agile method or framework can promote an Agile mindset and look at the importance of having an Agile mindset in the workplace. So as I say, we’ve got a really brilliant panel who’ve got really varied experience in relation to project management, and also in relation to the field that they work in. So I’d like to invite those to introduce themselves now. So could I invite Chris, first of all, please? Hi Chris.

Hey, good morning, everyone. My name’s Chris Humphrey. I work as a change delivery manager for Triodos Bank, so I work in financial services. A long time ago I did a PhD in medieval studies and a postdoc as well. About 20 years ago I left academia to pursue a career in people and project management in industry, most recently in financial services. Also on the side, I do run a little side project, Jobs On Toast, which is just where I share careers advice for PhDs and postdocs who are transitioning out of academia.

Thanks, Chris. Just for those of you who aren’t already aware of Chris’s work at Jobs On Toast, I really urge you to look at his LinkedIn page and website because he does share some really useful, illuminating content that would be really relevant to you guys given that Chris is a former postdoc himself. Could I invite Martin next, please?

Hi, yes. So my name’s Martin Squires. I’m a senior solutions consultant with Merkle. So basically, I do consulting projects in the marketing and customer data science space. Prior to Merkle, I ran my own business for a while, but I’ve also spent time as director of advanced analytics for Pets At Home, director of data insight and analytics at HomeServe, global lead for customer intelligence and data at Walgreens Boots Alliance, and head of customer intelligence and analysis for M&S Bank. So I’ve spent about 20 years putting together projects in the data science and analytics space.

Thanks, Martin. Thanks for being with us today. Could I invite Matina next, please?

So good morning, everyone. My name is Matina Tsalavouta. I thank you for inviting me here today. I work here at the University of Liverpool currently and for the last five years. In total, I have more than 20 years of experience in the higher education and research-intensive institutions. Ten years of those 20 years I was working as a researcher myself. My last research employment was at the University College London as a postdoc, with a Marie Curie Fellowship and Wellcome Trust Award. Then I moved into the strategic functions within research-intensive institutions where I used significant project management tools. I was the head of research, communications, and engagement for Rothamsted Research, a BBSRC strategically funded institute. Then I came here five years ago to be the head of research and impact communications for the university as a whole. Then I moved on to be the head of strategic planning and engagement for the Liverpool Cancer Research Institute. So yes, I look forward to discussing today and sharing some of the experiences and learning I have from my career.

Thanks very much, Matina. Rebecca, last but not least, would you like to introduce yourself, please?

Yes, of course. Good morning, everybody. So my name is Rebecca Douglas, and I am group programme director for talent at IPG Health Medical Communications. Very briefly, a bit of my background. I did my undergraduate at Liverpool, in applied genetics, and I did a PhD at Manchester in neuroscience, specifically within diabetic neuropathy. Then I moved into the medical communications industry as an entry-level medical writer. Worked my way through many, many iterations of the medical writing side of things, working with pharmaceutical companies to partner with them on their communication of pharmaceutical products and devices. For the last three years, I’ve been working in actual talent development. So the continual professional development of our talented people across the industry, which involves both the scientific staff, but also client services side. So lots of project management. Project management and Agile mindset is really key to everything that we do. So that’s why I was interested in this session, and really looking forward to it.

Thanks very much, Rebecca. Also, I’d like to invite all of our postdocs to introduce themselves in the chat, please. Perhaps just let us know your discipline and your reason for coming today, or your knowledge of project management, or just some insight into why you’re here today. Okay, brilliant. Thanks, everyone. So let’s move on to the first substantive part. So we thought it would be useful, first of all, just to spend about 20 minutes just really exploring what project management is and why it matters because, similar to research I suppose, that’s not an easy answer. There are varying different definitions, varying different approaches to project management, and various different understandings of what a project means. So I’ve given just a really boilerplate definition from the Association for Project Management, the APM website, about what a project is. They state that, ‘Projects occur when an organisation wants to deliver something to set requirements within an agreed budget and time frame.’ So what that’s getting at really is, just something very basic. A project is something that needs to deliver something within limited resources, be that time or money. I think we can all relate to that rather high-level definition. Some other things that we think are useful to explore in relation to projects are that historically, and probably still, a project is contrasted with what we call business as usual. So when I first learned about project management probably about 15 years ago, the standard model that you’d be given is comparing a project with business as usual, and a project would all be about managing change, delivering value, and business as usual is the everyday activity that you do as part of an organisation. In discussion with the panel in preparation for this session, I think one of the things that came out, and one of the reasons why project management’s so important, is that there’s no such thing as business as usual really anymore, or at least the rate of change in society, and in the economy, and in a variety of organisations is so vast now that projects, and managing change, and managing the new, has become the norm really rather than the exception. So that’s one thing that we’d like to explore and get everybody’s thoughts on. The second point is we will touch a little bit today on the difference between Waterfall and Agile approaches to project management. You’ll notice, as in lots of areas, it seems to be that if you look at the literature there appear to be two camps, two different broad ways of approaching projects. That certainly is the case, but also, we’ll reveal from speaking to the panel that there are lots of hybrid methods and these two approaches aren’t necessarily as distinct as might seem in the literature. Finally, another thing for us to think about today, and we’ll explore this more in the final session, is that the reason probably why project management matters so much is in part because it’s so prevalent in the world of work, and not only beyond academia, but project management skills are really important within research as well. Having spoken to all of our employer stakeholders at Prosper, and I’m sure our panel can certainly attest to this today, that kind of mental agility and adaptability that is required within project work, possibly more than other types of work, is a really vital skill mindset, competency, that will set you apart, shall we say, in the employment market. So I’d just like to open that out to the panel to see if there are any general comments about any of these key themes before we explore some of the differences between research and project management in more detail. Please feel free to shout out. I can see Martin’s unmuted.

Sorry, yes. Certainly, the bit that echoes for me is that the piece around project management is now effectively business as usual. Pretty much the last two or three organisations I’ve worked in, data science has increasingly become about producing data products in Agile terminology, or product management terminology. So we have a product output, whether that’s a segmentation model, whether it’s a propensity model, whether it’s a BI dashboard, and we tend to put people into Agile. The organisations tend to vary in what they call them as to whether they’re pods, they’re scrums, or how they want to describe them, but effectively pulling a cross-functional team together to deliver an output via a usually Agile methodology for stakeholders has become 80 per cent of the team’s deliverables. So it very much has become the standard way of working within a lot of data science teams.

Thank you for that, Martin. I don’t know about everybody else here, but I can’t necessarily relate to all of the different terminology as opposed to the different methods, but what I’m getting from that is that project management is really, really prevalent. Could you say something to that perhaps, Chris, in regards to your role?

Yes, I think it’s a good distinction that you make between project management and business as usual. I guess in the older way of thinking about it 80 per cent of what an organisation did could be read from a handbook or from a process. The same things were done every day. Then there was this smaller part of the organisation that tried to do projects and prepare the organisation for changes. Could be new products coming up, or new regulations, or some external change. I think, just reflecting on what Martin was saying, because especially in the last few years with Brexit, and with the pandemic, the rate of change is such, and also commercial cycles are getting shorter and shorter, that more and more of the organisation is working in the change area in terms of like you said, reacting to the new, rather than just following a script, or following a set process, or a set model. So I think whereas certainly when I started, I was the project manager, it was a more relatively niche thing, now those skills are really required by a lot of people across the organisation. Like Martin says, you’ve not got a little silo of the project management teams doing the change, but actually, you’re pulling lots of people from the business as usual into those teams to deliver the changes and prepare for what’s coming up. So I think that’s certainly an important shift to bear in mind.

Thanks very much for that, Chris. We have discussed in preparation for this session as well, which I should have mentioned earlier actually, that as well as project management being within a particular niche within an organisation, it may have been that historically with the PRINCE2 methodology or what we might call the Waterfall methodology, project management was primarily or largely used for things like large-scale construction projects, and high-risk things perhaps, or high-budget things that really needed that close risk management and detailed planning. Whereas now you can use a project approach to a very small project like, for example, the creation of a dashboard like Martin mentioned earlier. Of course, project management has increasingly been adopted within the research environment as well. So I wonder if you could speak to that, please, Matina?

Yes. Thank you, Katie. Obviously, we discussed previously about this, and I have been also reading a little bit the information that the postdocs that joined us here today, and it seems that there is quite a lot of interest to see how the project management skills from the research experience could translate in a professional role, or how project management skills could enhance the research activity. I personally believe that there are a lot of parallels certainly with the Agile methodology. So there are two fundamental principles in the Agile methodology of the flexible, iterative way of developing a solution, a product, and of course, the minimum viable product to start with. I think in research, especially the experimental research, and there are a few people here with us today from that point of view, they have experienced this. So you have a hypothesis, a question, you design an experiment, you do your experiment, you get your results, you look at it, and then you refine your methodological approach to progress with your research question. Recognition and acknowledgement of doing this while you’re doing it, naming it as part of an Agile way of working, helps build the skill set and being able to build that narrative when it comes in a professional setting, in a different role, in a role where project management might be the essence of the professional work. So I can definitely see quite a lot of parallels and I hope we will explore some in the rest of the day.

Thank you for that, Matina. I think there’s a couple of points there that really stand out to me, and I think we’ll be exploring these in a little more detail later as well. The first is this concept of minimum viable product. Getting something out that’s valuable as soon as possible rather than waiting for something to be perfect before putting it out, which in some ways perhaps we can contrast with the more predominant approaches within research, where it’s about perfecting something and submitting it for publication. You may disagree with that characterisation, but we can discuss that later. The second point that you raise that’s really important is this idea of iteration related to minimum viable product of doing something and then improving on it, and then improving on it, which I guess perhaps, I’m not a scientist, but perhaps the scientists here can relate to that kind of method in particular. We did talk, didn’t we Chris, because I know you have a humanities background, about how this kind of iteration and continuous improvement is relevant to research in the humanities as well, and perhaps those who’ve done that can apply that to project management.

Yes, that’s right. I think it’s a good point that you make that certainly when you think about a lot of academic outputs, there is an importance on the finished article, whether it’s the journal article, or the book, or something like that. Yes, I think it’s interesting, say within something like I studied, within history, often you’re doing takes on something based on what evidence you’ve got in a certain conclusion that you’ve come to, but there could always be new evidence emerging from the archives, or the research of other historians, or other scholars who can then lead you to change your focus and perspective. So, I can really see in the longer-term how a more humanities view, you can also express that in quite Agile terms, but perhaps the timescale is something slightly different compared with, like myself and Martin might work in quite short cycles within industry, but maybe within academic humanities, you could imagine a longer, more Agile mindset over years rather than weeks or months.

That’s an interesting way to think of it – thank you, Chris – thinking about the timescale and the overtime. Thank you. Finally, Rebecca, any sort of further comments you’d like to add in relation to the med-comms industry in particular or your own experience?

So within the med-comms industry, we partner with the client on their communication strategy, and feeding into that strategy is always multiple projects that are running side by side. There’s crosstalk between the different projects but ultimately, we have to get to our end points and there’s a timeline, and there’s a scope of work, and so project management is really integrated into absolutely everything that we do. It’s really, really critical to make sure that we’re meeting the client’s requests within the budget and timeline that we’ve got. That flexibility, and that ability to react to what’s happening within each project, is really important because we might get a new data set that has to be fed into that project. There might be a change of client and a change of direction on the project, but often the hard stop, the deadline doesn’t change. So having that Agile mindset and being able to work to the constant change, and the constant evolution of a project is really, really important within med comms. It’s often the thing that people find the hardest when they enter the industry because running multiple projects side by side and keeping everything going, and reacting, and changing, and sometimes going round in a little circle and then moving forwards, is just integrated into everything we do and is really, really key for success.[END OF TRANSCRIPT]

Watch our employer panel share their own views on research and project management in the following video.

Okay, thank you to everyone for that first part. Now we’re going to move into the meaty part of the workshop and look at some comparisons between research and project management across some key parameters, including the ones that were included within the pre-work. What I’m going to do here is I’m going to stop presenting because I’m going to adjust this PowerPoint live as we’re discussing. Basically, the first thing that I thought is really useful, or we all thought is really useful to look at, is looking at risk tolerance and the levels of uncertainty in research and in project management. I’ve just shared with you here some of the comments that we had from the pre-work just to give you an impression of the real variety of perceptions around this, all of which are valid actually. One participant has shared that project management is high risk of financial loss and research is high risk in terms of promotion prospects and the reception of further funding. That’s interesting, so we’re looking at – yes, the context within research and project management happens and I guess comparing the organisational risk with the personal risk or the risk to one’s career. Another comment that we’ve had is, ‘When thinking about risk, it depends on the type of research and project management you are undertaking. This is not an easy one to answer.’ That’s absolutely fair enough, I think. We’re talking in really broad strokes, general terms here, and of course, there’s a lot of variety in reality. Then a final comment: ‘Project management has a lower risk since preliminary work is done and requires to deliver something valuable. However, research does not always deliver the desired results that were first established.’ I think that’s a really good point as well because that highlights how the active management of risk is often a very important part of project management whereas it isn’t necessarily historically, in research. Although I would argue that that is probably happening more and more within research. Okay, so just to do something a little bit practical then, I thought we could just… Yes, some of the parameters around this discussion, and ask the panel to place where they would put research and project management on each of these continuums. Then we can compare it with what came through from the pre-work. Maybe I’ll put all of it together and share with you at the end of this workshop, but I thought we could start from scratch for the panel and get everybody’s take on this. I’ve grouped these three ones together because they’re quite related, I think. ‘Detailed plan’ versus ‘Seeing how things go’. ‘Well-defined goals’ versus ‘Exploring the unknown’, and ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’, but what I should actually have put there is ‘Low-risk tolerance’ and ‘High-risk tolerance’, how actively risk is managed, I suppose, as opposed to how risky the activity is. Rebecca, would you like to comment on that first? Just because I’m conscious you’ve always been last but not least. First but not least now.

Wasn’t ready to unmute then – I was expecting to be last!

Sorry!

Yes, so I would put much more towards the detailed plan side of things.

For project management?

Yes.

Yes, about here?

Yes.

Yes.

Well-defined goals I would put in a very similar place, actually!

Yes, okay.

I don’t think anything is risk-free. I don’t think anything is low risk, even when you’ve got the best project plan in the world, so I would probably put the next one just a little bit further to the right.

Maybe here?

Yes.

Yes, brilliant, and would you like to compare that with research or are you happy just sticking with project management?

Going back to scientific research, which was many years ago for me, I would probably put it in the middle for the top one.

Yes.

I would put it to the left for the next one down.

So more to the left than project management or less, about the same…?

No, less, I would say.

About here?

Yes, somewhere there, I would say.

Yes.

Then I would put the risk more to the centre.

Great, so again, here, okay.

Yes.

Thank you for that, Rebecca. Anybody else from the panel care to share where they would place these tokens?

I would probably place the project management ones around where the research one is on ‘Well-defined goals’ and ‘Detailed plan’. That’s just because in a number of projects… Oh, sorry, the one further to the left than that.

Oh, sorry.

I’m trying to point at the screen. That’s no good, is it?

This one?

There, yes, I’d put both ‘Detailed plan’ and ‘Well-defined goals’ there. I think that’s because sometimes you can get plans which… For example, a marketing director may know they want to implement a new customer experience system. They know what they want it to do, but it’s very difficult to actually get the detail around what exactly does that mean. You’ll often set off with something a little more agile, but we know it’s in this direction. The risk one I find really difficult because it would vary by project. For example, I’ve definitely been involved in some projects where there’s not an awful lot of risk if it does go wrong, and we can take a more aggressive approach to risk. However, I have worked on projects like implementing GDPR standards, and it’s like there is absolutely zero risk tolerance within organisations to that. I’ve literally worked on projects that have been absolutely with project management at both ends of that spectrum, so I’d say it’s totally dependent on the actual project.

If you’re comfortable, Martin, I’ll put that in the middle and make a note of that because I think, yes, that’s really important. I think one of our postdoc participants identified that as well. Yes, it really does depend on the project, and you’re talking about when it’s a kind of legal – about legal compliance…

Legal and regulatory, yes, so compliance with the Data Protection Act, absolutely zero risk tolerance in organisations. However, if you’re building a customer segmentation, if it goes wrong, well, you have another go, basically! You’ve got a far more open attitude to risk. You can try a new technique and if it doesn’t work, you just try another one. It causes a slight delay but generally, you’ve got a more open environment in certain project areas. Yes, there’ll always be legal and reg ones that are right over on the left-hand side.

Yes, okay. I’m going to put two down just so I can capture that variety rather than just plonk everything in the middle.

Yes, yes.

Would it be fair to say, though, that even if something is not as high risk as a regulatory or legal compliance project, would you agree or disagree that within a project management context, even if there is high risk, that an organisation would always seek to mitigate that risk, or do you think that there are more risk-taking approaches?

There’s less projects that have got a higher approach to risk, but they certainly do exist. Certainly, within one of the retailers I used to work for, we did a project looking at basically social media analytics and text-mining of social media data, and it literally was a: put somebody on this for a month. If they find anything interesting, wonderful. If they don’t find anything interesting, we’ve wasted a month of an analyst’s time, but we think there might be something in there – go, have a dig. Knock yourselves out. See what you can find. It’s rare you get a brief that’s that open, but they do exist, and you can get projects which are in the, yes, go dig – if you find something… The chances of you finding anything may be slim, but if you find anything, it could be absolute gold, so yes, go away and have a look, so they do exist. There’s less of them.

Yes, yes, yes. I guess I would say there, that would be great if you had the opportunity to do that, but actually, a month of an analyst’s time, it’s probably not that great a risk within the broader context of the organisation.

That’s it, yes, within the context of the organisation, the team at that time was 15 people, so putting one of them on that project for a month, it was time-bound and it was great if you find something, but if you don’t find anything interesting within the month, we just pull the plug and put the analyst on a different project. So it was constrained within that risk element but fundamentally, it was a punt, yes.

Thank you, Martin. I guess that leads us nicely into that comparison with research. I don’t know if you’re happy to do the comparison with research here, but I’m going to contend…

Yes, I’m kind of a distance more removed than most from the research environment, and a lot of my involvement with research has been through things like the Consumer Data Research Centre. Again, we would have approached it – the projects that I’ve used in retailers with that tended to be that sort of project. One of the ones we looked at was in terms of use of geography, does physical geography – because most of the geographic targeting is geodemographics and human geography. We looked at whether physical geography made any difference. In particular, we were looking at things like if you live next to electricity pylons, do you have a different attitude to risk? If you live over radon gas deposits… Now, again, that was a: if this finds nothing, I’ve kind of blown a very small involvement with CDRC internally. I’m not going to get fired for that. So basically, where I’ve tended to be involved is higher risk stuff because I’m not burning that much resource, but again that’s a peculiarity of the way that I’ve worked within organisations. I think again that’s meant that it’s – yes, I’d put it about there. Yes, that looks good.

I’m trying to push you into saying that research is high risk basically, but I don’t know in fact if you’d agree with that!

Yes, that’s fine. Again, the way I’ve used it – explore the unknown has been… I’d put the goals in about the same place because again we’ve tended to approach it as an adjunct to what was being done internally. It tends to be the: I’d love to put somebody on this internally but I don’t have the resource, but if I go down a route of working with academic institutions, I can kind of justify the investment. I think the detailed planning is closer to the middle because actually the students we’ve been involved in still need to actually pass the exams they’ve been set. You can’t exactly go, ‘Yes, just knock yourselves out,’ because the supervisor for dissertations is going to go, ‘Behave yourself, Squires. Sort out a plan. There’s going to be an exam at the end of this,’ sort of thing, so I think that one’s closer to the middle. As I say, it’s a peculiarity of how I’ve worked with CDRC.

No, that’s really useful. Thank you, Martin. This is shaping up to be quite an interesting visual. Chris, would you care to share your thoughts?

Yes, sure. I think it’s only because I worked in financial services for the last 11 years or so that I would… a lot of what we do is, like people have already said, it’s a very highly regulated industry, so we are having to meet specific deadlines. By this time, you must have implemented X or Y regulations, so I really think that a lot of our work is to the left on detailed plans, well-defined goals, really managing risk right down because we’ve got to hit those targets. Otherwise, you can risk fines or you’ll lose your licence to trade, that type of thing, and so I would put a lot of things over on the left. If I reflect on my own background as a humanities researcher, then I can think, yes, see how things go – I like that. I think it’s interesting in the humanities because you probably start off with a research question like: what’s the relationship between a festive culture and popular politics in late mediaeval England? That was what my PhD was on, so there’s a question and then you’re trying to look at the evidence base for where can you find linkages between those things, influences, which one is determining the other. So to me, it would be much more over on the right – you’re seeing how it goes, exploring the unknown by answering these questions. I think implicitly then you have a much higher risk in terms of… I was thinking, well, what is at risk in a PhD or a postdoc, but often it is: are you going to finish on time? Are you going to deliver results, an argument, a conclusion? Some of those things are the things at risk.

Thank you, Chris.

I guess the only other thing I would just say is that to me, project management itself is a way to manage risk, so when you apply a project management methodology to something, it is with the intention of lowering the risk. You can let people just get on with it, but that’s why we don’t because we apply project management because we perceive this to be risky, or have risk, and so we want to get that risk rating down towards the left, so project management’s always applied to something as a way to reduce risk in itself.

Okay, that’s interesting. I hadn’t thought of it in that way. Would you say that it’s more about a way of managing risk than a way of capitalising on an opportunity?

Yes, can be both. That is a good point. It can be both. I guess I’m a little bit thinking more from that point of view. Like I was saying before, we have to meet a deadline for implementing a regulation or to comply with something. In that case, it is about managing that risk, but yes, it’s a good point if you think about it from the point of view of capitalising on an opportunity, but again, you want to maximise the likelihood that you will capitalise on that opportunity, so again, you’re trying to de-risk it by applying project management principles.

Yes, thanks, Chris. Okay, this is really interesting. It’s actually looking like we’ve got a clear trend here with project management on the left on the more planned side, and research in contrast to that on the freer side, which I guess we probably would have expected. But I’m interested in Matina’s view and especially whether you think, Matina, that an Agile approach, as opposed to a more regulated approach to project management, might complicate this picture a little bit, given your experience of both.

Yes, thanks, first of all, I completely agree with Chris’s last point. This was a very good point that we use project management really to de-risk effectively what we are trying to do in any business setting. With regard to research, I think it depends a little bit… Of course, we try to generalise here, but it depends a little bit on the type of research and the activity within the research project, starting from the risk point of view. If, for instance, you’re doing clinical research and you are dealing with human samples, the process of getting those, everything is highly regulated. The tolerance for risk is extremely low to none, so the process of doing this would be, yes, exactly where you put it. On the other hand, if we are talking about the hypothesis and trying to identify, find something new, the research endeavour in itself, it seems that it is high risk, but if you think for a moment, is it truly high risk? If we don’t know, we are looking for an answer, whatever the answer is. If we have a predetermined view of what the answer is, then this is not research, what we are doing. Therefore, in my view, doing research is not necessarily – and it might sound controversial, this – it’s not really high risk. It’s just that you are looking for the unknown, but that’s why you’re doing research. You don’t know the answer. If you know it and you want a certain set of data, then this is not, in my view, research. So I would question the high-risk bit, and this is – I think one of the panel members mentioned ultimately the purpose is not what the answer will be, but it is that you conclude your project in time, your PhD, and within that, of course, there will be some findings. You may have what we call negative results to your hypothesis, but this is a finding and increasingly, we look to value this more in the research environment. That kind of takes away the sense of risk or reduces the risk as well conceptually, I think. With regards to well-defined goals, again, the same. The well-defined goals – if the goal is to finish your PhD or to finish your postdoc within the timeframe of your fellowship or your grant, then you have well-defined goals. If you are looking for certain specific answers, then maybe it’s not particularly a research project. Detailed plan – you do have a plan, but it can be iterative and again, this is the development of a research methodology, and it applies, I believe, in all disciplines. We kind of made that point, so that’s how research progresses as well. You have your question. You develop the methodology but also, you reach the endpoint of finding out the answer to what you asked. So a detailed plan I tend to be more at the lower end. There is this kind of Agile way of seeing this!

Are you happy with the middle? Does the middle sound…?

No, I would put it a little bit further, as I look at it, to my left.

This way?

Yes.

Yes, see this is interesting actually, Matina. You’ve got the most recent active research background and you’ve actually brought the research – you’ve moved the research more to the more planned, less risky side. Which is interesting because actually, this brings us to sharing and looking a little bit about the response of some of our postdoc participants here today because actually, there was a real variety across here. There wasn’t, I don’t think, a really… I don’t think there was as clear a distinction between PM and research. I’ll quickly – I will share a collated version of this with you guys after today, but just as an example, if you look at the top, can you see that? What can you guys see at the moment?

The same slide from previously.

Oh, okay, all right. I’m not… I tell you what, I’ll share it at another time, but what I can say is that a lot of the participants who shared the pre-work, some actually put research more to the left than project management. I thought that was quite interesting and we’ll share that with everybody after the session. Could I ask now for any of the participants, especially those who completed the research, if they’d like to speak up and share their thinking or any reflections, whether their thoughts have changed based on hearing this discussion from the panel members or any comments or questions at all from our postdocs? Feel free to just speak up because I can’t actually see…

Yes, hi, my name’s Rosa and yes, I’ve been working in research for more than 15 years now. I think I agree with Martina definitely, but the research depends on the project. I’ve been on applied projects. Actually, I am on an applied project because I do biotechs and I do biology now, but I’ve been also on a discovery project. The discovery project is more about how things go, because you can make a plan. I’ve been and discovered something. Obviously, I need to do the experiment, discover a piece of the puzzle and then I need to go back on it and try to help that puzzle. This can be very time-consuming, can be high risk because, although you have a negative answer to your question, as Matina would say, it’s still data, but sometimes you cannot publish it. For me, this is high risk because especially in my career, if I am a postdoc, of course, I don’t have the PhD to finish so it’s no more than like a title, but to get credit on my work, so that’s my risk. That is high risk, but now that I am on an applied project, obviously, the plans have more details because I know what I am looking for. Then it’s just to show if my idea is correct or not, so everything moves very fast because you can go in the lab and do the experiment. Okay, it didn’t work – let’s move on to something else…

Thank you for that, Rosa, yes. Sorry, carry on – I thought you’d finished.

Oh, no, I was going to say I think it depends – can be on the left, on the right of research. Really depends on the kind of project that you are working on, I think.

Yes, yes, and I’m interested to know if our postdocs agree that more of a risk management, perhaps project management informed approach to research delivery, if they perceive any increase in that or any trend towards that approach at the moment. Just shout out or…

Yes, for me personally, it does, for example. I have noticed it. I’m trying to… I manage a lot of PhD students now and I’m trying to make them to understand that probably it is because for me now, as I said, from my experience it’s all about project management even when you do research. I think we do research because we love it obviously, but if often we are just focused on going to the lab and do a lot of data, at the end of the day, you are on your desk with so much of your data that you don’t know how to put them together and this doesn’t really give you a final paper that you can publish. I think we should have more of the mind that says, okay, I would like to do this. However, it’s… I also think these days it depends on the demand of what also… It’s all about bio-illumination these days, and try to be on a green environment, so a lot of research has happened over there as well, so that’s my own…

Just food for thought, just a couple of things that came to mind when you were talking. Is there something about research that if…? I personally don’t think that if every researcher adopted a project management approach, that would be the best thing. There are some benefits of a project management approach, but there are probably some negatives as well, especially in a research context. You do want to be able to see how things go, in some ways, but then… Yes, I wonder if the panel have any thoughts on that.

I think within any good team, being able to play to the strengths of the individual is really important. Some people are natural project managers and they do it really well, and within a research environment, it’s their thing and they push things on, and they act in that way. Then there are at the other end of the spectrum people who are much better at seeing how things go and can live with the risk of that and everything else. I think, as you form your teams, it’s really important to think about the mix of people within that team so that you get a good balance, in my view.

[END OF TRANSCRIPT]

Watch our panel discuss the nature, importance and prevalence of project management below.

Okay, thank you to everyone for that first part. Now we’re going to move into the meaty part of the workshop and look at some comparisons between research and project management across some key parameters, including the ones that were included within the pre-work. What I’m going to do here is I’m going to stop presenting because I’m going to adjust this PowerPoint live as we’re discussing. Basically, the first thing that I thought is really useful, or we all thought is really useful to look at, is looking at risk tolerance and the levels of uncertainty in research and in project management. I’ve just shared with you here some of the comments that we had from the pre-work just to give you an impression of the real variety of perceptions around this, all of which are valid actually. One participant has shared that project management is high risk of financial loss and research is high risk in terms of promotion prospects and the reception of further funding. That’s interesting, so we’re looking at – yes, the context within research and project management happens and I guess comparing the organisational risk with the personal risk or the risk to one’s career. Another comment that we’ve had is, ‘When thinking about risk, it depends on the type of research and project management you are undertaking. This is not an easy one to answer.’ That’s absolutely fair enough, I think. We’re talking in really broad strokes, general terms here, and of course, there’s a lot of variety in reality. Then a final comment: ‘Project management has a lower risk since preliminary work is done and requires to deliver something valuable. However, research does not always deliver the desired results that were first established.’ I think that’s a really good point as well because that highlights how the active management of risk is often a very important part of project management whereas it isn’t necessarily historically, in research. Although I would argue that that is probably happening more and more within research. Okay, so just to do something a little bit practical then, I thought we could just… Yes, some of the parameters around this discussion, and ask the panel to place where they would put research and project management on each of these continuums. Then we can compare it with what came through from the pre-work. Maybe I’ll put all of it together and share with you at the end of this workshop, but I thought we could start from scratch for the panel and get everybody’s take on this. I’ve grouped these three ones together because they’re quite related, I think. ‘Detailed plan’ versus ‘Seeing how things go’. ‘Well-defined goals’ versus ‘Exploring the unknown’, and ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’, but what I should actually have put there is ‘Low-risk tolerance’ and ‘High-risk tolerance’, how actively risk is managed, I suppose, as opposed to how risky the activity is. Rebecca, would you like to comment on that first? Just because I’m conscious you’ve always been last but not least. First but not least now.

Wasn’t ready to unmute then – I was expecting to be last!

Sorry!

Yes, so I would put much more towards the detailed plan side of things.

For project management?

Yes.

Yes, about here?

Yes.

Yes.

Well-defined goals I would put in a very similar place, actually!

Yes, okay.

I don’t think anything is risk-free. I don’t think anything is low risk, even when you’ve got the best project plan in the world, so I would probably put the next one just a little bit further to the right.

Maybe here?

Yes.

Yes, brilliant, and would you like to compare that with research or are you happy just sticking with project management?

Going back to scientific research, which was many years ago for me, I would probably put it in the middle for the top one.

Yes.

I would put it to the left for the next one down.

So more to the left than project management or less, about the same…?

No, less, I would say.

About here?

Yes, somewhere there, I would say.

Yes.

Then I would put the risk more to the centre.

Great, so again, here, okay.

Yes.

Thank you for that, Rebecca. Anybody else from the panel care to share where they would place these tokens?

I would probably place the project management ones around where the research one is on ‘Well-defined goals’ and ‘Detailed plan’. That’s just because in a number of projects… Oh, sorry, the one further to the left than that.

Oh, sorry.

I’m trying to point at the screen. That’s no good, is it?

This one?

There, yes, I’d put both ‘Detailed plan’ and ‘Well-defined goals’ there. I think that’s because sometimes you can get plans which… For example, a marketing director may know they want to implement a new customer experience system. They know what they want it to do, but it’s very difficult to actually get the detail around what exactly does that mean. You’ll often set off with something a little more agile, but we know it’s in this direction. The risk one I find really difficult because it would vary by project. For example, I’ve definitely been involved in some projects where there’s not an awful lot of risk if it does go wrong, and we can take a more aggressive approach to risk. However, I have worked on projects like implementing GDPR standards, and it’s like there is absolutely zero risk tolerance within organisations to that. I’ve literally worked on projects that have been absolutely with project management at both ends of that spectrum, so I’d say it’s totally dependent on the actual project.

If you’re comfortable, Martin, I’ll put that in the middle and make a note of that because I think, yes, that’s really important. I think one of our postdoc participants identified that as well. Yes, it really does depend on the project, and you’re talking about when it’s a kind of legal – about legal compliance…

Legal and regulatory, yes, so compliance with the Data Protection Act, absolutely zero risk tolerance in organisations. However, if you’re building a customer segmentation, if it goes wrong, well, you have another go, basically! You’ve got a far more open attitude to risk. You can try a new technique and if it doesn’t work, you just try another one. It causes a slight delay but generally, you’ve got a more open environment in certain project areas. Yes, there’ll always be legal and reg ones that are right over on the left-hand side.

Yes, okay. I’m going to put two down just so I can capture that variety rather than just plonk everything in the middle.

Yes, yes.

Would it be fair to say, though, that even if something is not as high risk as a regulatory or legal compliance project, would you agree or disagree that within a project management context, even if there is high risk, that an organisation would always seek to mitigate that risk, or do you think that there are more risk-taking approaches?

There’s less projects that have got a higher approach to risk, but they certainly do exist. Certainly, within one of the retailers I used to work for, we did a project looking at basically social media analytics and text-mining of social media data, and it literally was a: put somebody on this for a month. If they find anything interesting, wonderful. If they don’t find anything interesting, we’ve wasted a month of an analyst’s time, but we think there might be something in there – go, have a dig. Knock yourselves out. See what you can find. It’s rare you get a brief that’s that open, but they do exist, and you can get projects which are in the, yes, go dig – if you find something… The chances of you finding anything may be slim, but if you find anything, it could be absolute gold, so yes, go away and have a look, so they do exist. There’s less of them.

Yes, yes, yes. I guess I would say there, that would be great if you had the opportunity to do that, but actually, a month of an analyst’s time, it’s probably not that great a risk within the broader context of the organisation.

That’s it, yes, within the context of the organisation, the team at that time was 15 people, so putting one of them on that project for a month, it was time-bound and it was great if you find something, but if you don’t find anything interesting within the month, we just pull the plug and put the analyst on a different project. So it was constrained within that risk element but fundamentally, it was a punt, yes.

Thank you, Martin. I guess that leads us nicely into that comparison with research. I don’t know if you’re happy to do the comparison with research here, but I’m going to contend…

Yes, I’m kind of a distance more removed than most from the research environment, and a lot of my involvement with research has been through things like the Consumer Data Research Centre. Again, we would have approached it – the projects that I’ve used in retailers with that tended to be that sort of project. One of the ones we looked at was in terms of use of geography, does physical geography – because most of the geographic targeting is geodemographics and human geography. We looked at whether physical geography made any difference. In particular, we were looking at things like if you live next to electricity pylons, do you have a different attitude to risk? If you live over radon gas deposits… Now, again, that was a: if this finds nothing, I’ve kind of blown a very small involvement with CDRC internally. I’m not going to get fired for that. So basically, where I’ve tended to be involved is higher risk stuff because I’m not burning that much resource, but again that’s a peculiarity of the way that I’ve worked within organisations. I think again that’s meant that it’s – yes, I’d put it about there. Yes, that looks good.

I’m trying to push you into saying that research is high risk basically, but I don’t know in fact if you’d agree with that!

Yes, that’s fine. Again, the way I’ve used it – explore the unknown has been… I’d put the goals in about the same place because again we’ve tended to approach it as an adjunct to what was being done internally. It tends to be the: I’d love to put somebody on this internally but I don’t have the resource, but if I go down a route of working with academic institutions, I can kind of justify the investment. I think the detailed planning is closer to the middle because actually the students we’ve been involved in still need to actually pass the exams they’ve been set. You can’t exactly go, ‘Yes, just knock yourselves out,’ because the supervisor for dissertations is going to go, ‘Behave yourself, Squires. Sort out a plan. There’s going to be an exam at the end of this,’ sort of thing, so I think that one’s closer to the middle. As I say, it’s a peculiarity of how I’ve worked with CDRC.

No, that’s really useful. Thank you, Martin. This is shaping up to be quite an interesting visual. Chris, would you care to share your thoughts?

Yes, sure. I think it’s only because I worked in financial services for the last 11 years or so that I would… a lot of what we do is, like people have already said, it’s a very highly regulated industry, so we are having to meet specific deadlines. By this time, you must have implemented X or Y regulations, so I really think that a lot of our work is to the left on detailed plans, well-defined goals, really managing risk right down because we’ve got to hit those targets. Otherwise, you can risk fines or you’ll lose your licence to trade, that type of thing, and so I would put a lot of things over on the left. If I reflect on my own background as a humanities researcher, then I can think, yes, see how things go – I like that. I think it’s interesting in the humanities because you probably start off with a research question like: what’s the relationship between a festive culture and popular politics in late mediaeval England? That was what my PhD was on, so there’s a question and then you’re trying to look at the evidence base for where can you find linkages between those things, influences, which one is determining the other. So to me, it would be much more over on the right – you’re seeing how it goes, exploring the unknown by answering these questions. I think implicitly then you have a much higher risk in terms of… I was thinking, well, what is at risk in a PhD or a postdoc, but often it is: are you going to finish on time? Are you going to deliver results, an argument, a conclusion? Some of those things are the things at risk.

Thank you, Chris.

I guess the only other thing I would just say is that to me, project management itself is a way to manage risk, so when you apply a project management methodology to something, it is with the intention of lowering the risk. You can let people just get on with it, but that’s why we don’t because we apply project management because we perceive this to be risky, or have risk, and so we want to get that risk rating down towards the left, so project management’s always applied to something as a way to reduce risk in itself.

Okay, that’s interesting. I hadn’t thought of it in that way. Would you say that it’s more about a way of managing risk than a way of capitalising on an opportunity?

Yes, can be both. That is a good point. It can be both. I guess I’m a little bit thinking more from that point of view. Like I was saying before, we have to meet a deadline for implementing a regulation or to comply with something. In that case, it is about managing that risk, but yes, it’s a good point if you think about it from the point of view of capitalising on an opportunity, but again, you want to maximise the likelihood that you will capitalise on that opportunity, so again, you’re trying to de-risk it by applying project management principles.

Yes, thanks, Chris. Okay, this is really interesting. It’s actually looking like we’ve got a clear trend here with project management on the left on the more planned side, and research in contrast to that on the freer side, which I guess we probably would have expected. But I’m interested in Matina’s view and especially whether you think, Matina, that an Agile approach, as opposed to a more regulated approach to project management, might complicate this picture a little bit, given your experience of both.

Yes, thanks, first of all, I completely agree with Chris’s last point. This was a very good point that we use project management really to de-risk effectively what we are trying to do in any business setting. With regard to research, I think it depends a little bit… Of course, we try to generalise here, but it depends a little bit on the type of research and the activity within the research project, starting from the risk point of view. If, for instance, you’re doing clinical research and you are dealing with human samples, the process of getting those, everything is highly regulated. The tolerance for risk is extremely low to none, so the process of doing this would be, yes, exactly where you put it. On the other hand, if we are talking about the hypothesis and trying to identify, find something new, the research endeavour in itself, it seems that it is high risk, but if you think for a moment, is it truly high risk? If we don’t know, we are looking for an answer, whatever the answer is. If we have a predetermined view of what the answer is, then this is not research, what we are doing. Therefore, in my view, doing research is not necessarily – and it might sound controversial, this – it’s not really high risk. It’s just that you are looking for the unknown, but that’s why you’re doing research. You don’t know the answer. If you know it and you want a certain set of data, then this is not, in my view, research. So I would question the high-risk bit, and this is – I think one of the panel members mentioned ultimately the purpose is not what the answer will be, but it is that you conclude your project in time, your PhD, and within that, of course, there will be some findings. You may have what we call negative results to your hypothesis, but this is a finding and increasingly, we look to value this more in the research environment. That kind of takes away the sense of risk or reduces the risk as well conceptually, I think. With regards to well-defined goals, again, the same. The well-defined goals – if the goal is to finish your PhD or to finish your postdoc within the timeframe of your fellowship or your grant, then you have well-defined goals. If you are looking for certain specific answers, then maybe it’s not particularly a research project. Detailed plan – you do have a plan, but it can be iterative and again, this is the development of a research methodology, and it applies, I believe, in all disciplines. We kind of made that point, so that’s how research progresses as well. You have your question. You develop the methodology but also, you reach the endpoint of finding out the answer to what you asked. So a detailed plan I tend to be more at the lower end. There is this kind of Agile way of seeing this!

Are you happy with the middle? Does the middle sound…?

No, I would put it a little bit further, as I look at it, to my left.

This way?

Yes.

Yes, see this is interesting actually, Matina. You’ve got the most recent active research background and you’ve actually brought the research – you’ve moved the research more to the more planned, less risky side. Which is interesting because actually, this brings us to sharing and looking a little bit about the response of some of our postdoc participants here today because actually, there was a real variety across here. There wasn’t, I don’t think, a really… I don’t think there was as clear a distinction between PM and research. I’ll quickly – I will share a collated version of this with you guys after today, but just as an example, if you look at the top, can you see that? What can you guys see at the moment?

The same slide from previously.

Oh, okay, all right. I’m not… I tell you what, I’ll share it at another time, but what I can say is that a lot of the participants who shared the pre-work, some actually put research more to the left than project management. I thought that was quite interesting and we’ll share that with everybody after the session. Could I ask now for any of the participants, especially those who completed the research, if they’d like to speak up and share their thinking or any reflections, whether their thoughts have changed based on hearing this discussion from the panel members or any comments or questions at all from our postdocs? Feel free to just speak up because I can’t actually see…

Yes, hi, my name’s Rosa and yes, I’ve been working in research for more than 15 years now. I think I agree with Martina definitely, but the research depends on the project. I’ve been on applied projects. Actually, I am on an applied project because I do biotechs and I do biology now, but I’ve been also on a discovery project. The discovery project is more about how things go, because you can make a plan. I’ve been and discovered something. Obviously, I need to do the experiment, discover a piece of the puzzle and then I need to go back on it and try to help that puzzle. This can be very time-consuming, can be high risk because, although you have a negative answer to your question, as Matina would say, it’s still data, but sometimes you cannot publish it. For me, this is high risk because especially in my career, if I am a postdoc, of course, I don’t have the PhD to finish so it’s no more than like a title, but to get credit on my work, so that’s my risk. That is high risk, but now that I am on an applied project, obviously, the plans have more details because I know what I am looking for. Then it’s just to show if my idea is correct or not, so everything moves very fast because you can go in the lab and do the experiment. Okay, it didn’t work – let’s move on to something else…

Thank you for that, Rosa, yes. Sorry, carry on – I thought you’d finished.

Oh, no, I was going to say I think it depends – can be on the left, on the right of research. Really depends on the kind of project that you are working on, I think.

Yes, yes, and I’m interested to know if our postdocs agree that more of a risk management, perhaps project management informed approach to research delivery, if they perceive any increase in that or any trend towards that approach at the moment. Just shout out or…

Yes, for me personally, it does, for example. I have noticed it. I’m trying to… I manage a lot of PhD students now and I’m trying to make them to understand that probably it is because for me now, as I said, from my experience it’s all about project management even when you do research. I think we do research because we love it obviously, but if often we are just focused on going to the lab and do a lot of data, at the end of the day, you are on your desk with so much of your data that you don’t know how to put them together and this doesn’t really give you a final paper that you can publish. I think we should have more of the mind that says, okay, I would like to do this. However, it’s… I also think these days it depends on the demand of what also… It’s all about bio-illumination these days, and try to be on a green environment, so a lot of research has happened over there as well, so that’s my own…

Just food for thought, just a couple of things that came to mind when you were talking. Is there something about research that if…? I personally don’t think that if every researcher adopted a project management approach, that would be the best thing. There are some benefits of a project management approach, but there are probably some negatives as well, especially in a research context. You do want to be able to see how things go, in some ways, but then… Yes, I wonder if the panel have any thoughts on that.

I think within any good team, being able to play to the strengths of the individual is really important. Some people are natural project managers and they do it really well, and within a research environment, it’s their thing and they push things on, and they act in that way. Then there are at the other end of the spectrum people who are much better at seeing how things go and can live with the risk of that and everything else. I think, as you form your teams, it’s really important to think about the mix of people within that team so that you get a good balance, in my view.

[END OF TRANSCRIPT]

We review the four values of the agile manifesto and their relevance and applicability to a range of sectors.

Okay, let’s just make a start on this final section of today’s workshop or discussion. What we’re going to talk about now is looking particularly at Agile methodology, have a think about the relationship between methodology and mindset when it comes to project management. As a kind of prompt, primarily for our panel but also for our participants to have a look at, I’ve shared here the four values from the Agile Manifesto, which I’ll share with you afterwards as well. Just thinking back to what we said briefly about the waterfall versus Agile methodologies, as far as I understand it, the Agile methodology emanated from software development, so the people who made this manifesto were from that field. So you can see that a lot of their language is really relevant to that field and its applicability beyond that is varied and debatable, but basically, what they were trying to do, I think, is make project management a little bit more responsive to change than perhaps previous methodologies. I just wanted to explore that a little bit here and maybe to help us question a division that may be in our head between research and project management, and just show that Agile methodology in PM can be quite fast-paced, quite liberating and have some benefits as well as setbacks, of course. What we’ve got here are the four values, as I said, and what the manifesto states is that they do value the things on the bottom, but they value the things on the top more. What we’ve got are Individuals and Interactions over Processes and Tools, Working Software over Comprehensive Documentation – that’s probably the least relatable, obviously, beyond software development, but it may be something like working products, I don’t know, over the original plan or something like that. Customer Collaboration over Contract Negotiation, and Responding to Change over Following a Plan. I’d like to invite Chris, first of all, just to share any reflections on any of those and how that relates to your role, to your approach to project management.

Yes, I think it’s really interesting because I guess if you think, where did Agile come out of, people obviously thought there were risks in large-scale software projects and so they applied a more rigid project management framework to it, but then still found out that software projects weren’t delivering on time. They were taking too long and going over budget, and I think it comes from that process of reflection. Even if we apply all these controls, why aren’t we really achieving the goals? I think that’s where there’s a sort of step back and say, actually, we can’t necessarily know everything at the beginning that we need to know by the end. So what’s better is to actually not do 90 per cent of the work and then deliver the end result to the customer and say, ‘Is this what you want?’ and then they say, ‘Not really.’ It’s actually to start off and show something to the customer very early on: ‘Is this what you want?’ and then react to the customer, even if it’s a real customer, if it’s an external client or an internal customer. Then iterate, as it were, to keep creating new versions that take into account the customer feedback so that you’re more likely to get to what the customer wants within the timescale or even earlier. I think that’s a little bit of how I see it and that’s certainly the methodologies now that are used with a lot of organisations, even banks that rely a lot on software, like a mobile app or an internet banking portal. How do you deliver those changes but you’re making sure that you’re doing it on time and that it’s responsive to customer needs?

I think that number 3 has come through really strong there then, hasn’t it, Chris, for you, that importance of collaboration with the end user or the customer or the beneficiary if it’s in a charitable sector that you’re working, for example. Would anyone like to pick up on any of the other points? Of course, you did cover Responding to Change as well, Chris. How about you, Rebecca? I know you don’t use Agile necessarily in a strict sense, but I know that agility and responsiveness to change is really important in your organisation and industry.

Yes, we don’t use it in the strictest sense, but I would say that all of these things are… Maybe not the Working Software. I can see bits where that applies, but the rest of it I would say is just so applicable. Customer collaboration, talking to our clients, like Chris said, making sure that all the way along, we’re all going on the same journey and that we’re not getting to the end product and saying, ‘Is this what you wanted?’ because that can have a disastrous impact upon everything. So yes, even though we don’t work with it formally, I can see all of this in what we do every day.

Do you see any risk in focusing on the top values over the bottom?

You need all those bottom things – that’s important. That’s the mechanics of it, but day-to-day it’s almost like that bottom bit happens at quite a high level in our industry. The people making those decisions around contract negotiations and things – that’s away from the day-to-day team. Whereas the day-to-day team is all about the individual interactions, the customer collaboration, the responsiveness to change and having an Agile mindset. It’s almost like the day-to-day teams would just expect all of that stuff to be in place and for us to be following it. Comprehensive documentation is important because we work in a really highly regulated industry. It’s important that we’re all following the rules, that we’re transparent in how data is reported. That’s important, but it’s almost like that’s a given that we all do that. We have to do that, but all of the other stuff is what makes it happen well and it differentiates us in terms of how we deliver our projects and how we recover financially on them and all of that stuff.

For example, you mentioned earlier a natural project manager and that someone who’d do well has that Agile mindset, so what kind of thing…? How do you foster that within your organisation or how can postdocs think about developing that skill or how might they do it in your industry?