Policy

- Policy landscape

- Working in policy

- Policy career journeys

Policy and working in a cause-driven context is of interest to many postdocs. This is likely due to the close connection between research and policy. There is also an increasing focus on impact in research. Alongside, and often closely connected to policy, is working in a cause-driven organisation. Working in an organisation with a clear ethical or altruistic mission often appeals to postdocs.

During the Prosper pilots, we held a workshop with a range of employers working in policy and/or a cause-driven organisation. The employer contributors* were:

- Al Mathers (Director of Research and Learning at The RSA (The royal society for arts, manufactures and commerce)

- Gavin Wood (Manager of Disability Research – Children with Disabilities, at UNICEF)

- Edward Latter (Chemicals Policy Team Leader at the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs)

- Jennifer Jarman (Head of Monitoring and Evaluation at The Reader UK)

* roles accurate as of November 2022.

Each of the employers introduced themselves, their organisation and their roles within that organisation.

Welcome to this session, this rearranged session, all about policy, careers in policy and, relatedly, working in cause-driven organisations. I think most of you know me by now but my name’s Katie for those who don’t. I am one of our Stakeholder Engagement Managers on Prosper. We’ve got a brilliant panel, who all work in different ways and in different organisations in the policy landscape, to speak to us today. I’ll invite them to introduce themselves in a moment. Just a quick run-through of the session today. After we’ve done some introductions in a mo, I’ll just give a brief presentation outlining the perceptions of the majority of you who are here today of working in policy. As you know, you were invited to complete some pre-work in preparation for this session today, so we’ll just have a look at some of the key themes that came through for that just to set the context, really, for the session; and, hopefully, to get our panel’s take on whether they agree or disagree with some of your views. After doing that, I’ll just give a short presentation model about how we are talking about policy today, how we perceive it and all of the panel members working in different areas in relation to that model just to underpin the discussion. I’ll then be inviting the panel members to comment on the model and the different career paths and career opportunities and policy before a short break. The second activity that we’ll do is all about looking at research, specifically in a policy context and comparing and contrasting what research means in different contexts and the skills and aptitudes that we all think are required in different contexts for researchers. Finally, we’ll be inviting our panel to share some insights into their own career pathways in policy. We’ve got some really interesting ones and, hopefully, you’ll find that inspirational as well. Okay, so welcome, then, to all of our panel members and our participants. I’d like to invite our panel to introduce themselves, just briefly for now, in perhaps the order that we’ve got written here. So, Al if I can invite you first.

Yes, of course. Many thanks, Katie. As it says on the screen. I’m Al Mathers. I’m Director of Research and Learning at the RSA. The RSA stands for the Royal Society of Arts. I suppose my role at the RSA covers both policy but, also, a lot of different areas of research and practice that feed into that. I’ll pass to Gavin.

Thank you, Al. Yes, I’m Gavin Wood. I’m, well, I’m reading off the screen now, aren’t I? So, the Manager of Disability Research at UNICEF’s dedicated Office of Research which is based in Italy in Florence. I’ll look forward to sharing more about that as we get through this session. Over to you, Ed.

Thanks, Gavin. Hi, everyone. I’m Ed Latter. So, as it says on the screen, I head up the Chemicals Policy Team within Defra. So, policy within a central government organisation looking to develop and implement government policies. Thanks, and over to Jennifer.

Thanks very much, Ed. My name is Jennifer Jarman and I’m Head of Monitoring and Evaluation at a national charity which is headquartered in Liverpool. I’m feeding to you live from The Mansion House in Calderstones Park if any of you have ever been there. We’ll reflect a little bit later on what the Reader does if you’re not quite sure about that.

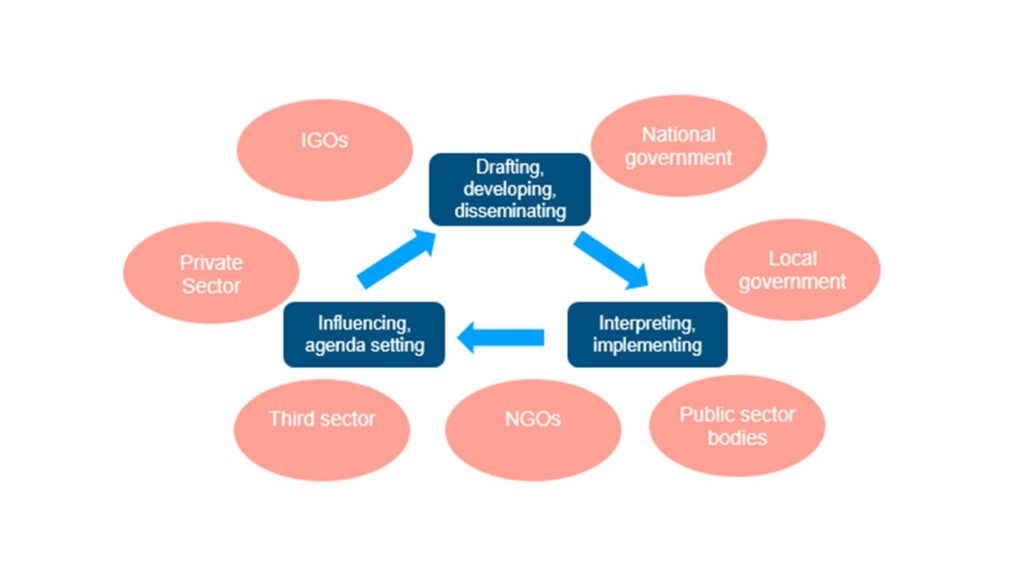

Thanks, Jen, and thanks very much to the panel for those introductions. Okay, so let’s look, then, at some of the perceptions of the participants here today of policy careers. One of the questions you were asked in preparation for the session was, ‘What type of activities do you imagine working in policy entails?’ Unsurprisingly, because it is such a varied field, we got a real variety of answers. The most common response was around the top one here, researching different options, actually drafting policies. Second, I think you all recognised the importance of stakeholder engagement and working with people when working in a policy context. Dissemination and communications, policy implementation, were also mentioned. The importance not only of researching but evaluating the impact of policy was highlighted. Several people put ‘Lobbying’ as well, which I think, yes, is a good thing to note. Interestingly, and totally understandably, several people put ‘Not sure, that’s why I’m coming to the session.’ Hopefully, we can demystify that for you a little bit today. You were also asked to highlight what you thought may be some of the key advantages or key highlights, as well as the key challenges of working in a policy context. There was quite a lot of consensus about these. I’d be really interested in what the panel think about these, whether you agree or not. So, by far, the top response, was really about real-world impact, making a tangible difference, seeing the impact on individuals. I think a couple of people mentioned that impact is increasingly important in the research context but it does, sometimes, feel a step removed. It was felt that policy was that closer to realising the outputs and the outcomes of the work. Several people commented on the fact that they were attracted to the career because of the intellectual stimulation aspect of it; so, learning a whole new ecosystem, thinking that there would probably be a lot of similarly intellectually-stimulating colleagues, and collaboration with colleagues came up quite a lot as well. A couple of people also, interestingly, mentioned this desire to support evidence-based policymaking. So, to play an active role in doing something that they felt, I guess, was important in policy. Then, challenges, again, there was quite a lot of consensus about this. Everybody, almost, mentioned that they envisaged the challenge of balancing multiple interests, multiple stakeholder interests and, related to that, politics or associated challenges were mentioned. I think people meant different things when referencing politics. Some people mentioned the fact that the work might often be reactive in response to political pressures and, perhaps, not as strategic as would be ideal. Others mentioned that the political environment in which you’re implementing policy would compel you to compromise on ideals which might be challenging. Then, interestingly, pace came up on both sides. So, slow pace and fast pace were identified as potential challenges, so we’d be interested to hear the panel’s thoughts on that. I know what I would say. Finally, because we’ve got several members of the panel who work in a cause-driven organisation, as well as a policy context, we were interested in your perceptions of working in that kind of organisation. These were the things that were highlighted. The vast majority commented that you thought you’d be attracted to this kind of work, that there’d probably be a high level of job satisfaction and related that to the real-world impact that you identified would be a possibility in policy as well. There were some concerns flagged. Firstly, about the potential for burnout. If you are really motivated by a cause, it might be difficult to draw up work-life balance boundaries around that. Also, challenges around funding which I think we can all recognise are a real problem. This was an interesting one, I thought. A point that came up several times was some thought that working for a cause-driven organisation might be monotonous because it’s about a single cause and there might not be much variety. It’d be interesting to see if any members of the panel have any comments about that. Before we move to that discussion, I think from the pre-work, I think it’s quite clear that a lot of you have quite a good knowledge of what it means to work in policy already. We thought it might be useful to just provide that grounding model around which we’re going to talk today. That’s what we’ve got here. We’ve divided it into three. There’s, on the one hand, what you may traditionally think of as policy work, as the drafting, developing and dissemination of policy. Related to that, you then have the organisations who interpret and implement the policy. Then, of course, you have the organisations, different bodies, who seek to set the agenda for policy making and to influence policy. I guess, you can imagine research coming into play in all of these. Perhaps, the last two more than the rest. I think it’s important to note that it’s not any one sector or any one organisation who wholly occupies any area of this triangle. There are lots of organisations and types of organisations that will be working within this feedback loop. Of course, you’ve got government bodies, so national government, local government, other public-sector bodies and intergovernmental organisations, who will all, perhaps, set policy, perhaps also seek to influence it; perhaps, be tasked with implementing it as well. Third-sector organisations and NGOs, I guess, would be both implementing and influencing policy. Also, setting their own internal policies. Then, of course, you have the private sector who may in their own organisations set internal policies but would also seek to influence government policy in favour of their own interests. That’s my take on it which has been run past our experts. I’m hoping that we can move on to them, giving a little more flavour to what that means in their context and to how they relate to this model here. I’m not going to pick on anyone. I’m going to ask if anybody would like to volunteer from the panel. Or maybe I will pick on someone. How about you, Al?

Yes, I’m very happy to come in. Obviously, other colleagues do come in and build on this. I think what’s interesting with this model here is this sets a lot of things at that organisation, or national, or system level. I think, and I’ll come on to this in more detail when I talk a bit more about the kind of work that I’ve been involved in, I think there’s a big thing around citizens and citizen voice which I suppose comes back to one of the previous slides, managing those different power dynamics. Actually, citizen voice and deliberative democracy… Whilst it may not be a sector or an organisation in its own right, it’s definitely a key dimension to capture, I would say, in this model here. I don’t know if there are other panellists who have further thoughts but that was what stood out for me.

Thank you, Al. Yes, I think that’s important.

I can jump in. I’ll just echo that. I think it is important. In the influencing agenda setting, in particular, there’s a lot of reach out to stakeholders and the key players. An important aspect of that – I’m working on this very same thing now on a disability research agenda – is to make sure that the loudest voices or the biggest wallets are not influencing that agenda and to have that democratic area. I think there is quite a lot of work in that space. I agree there is much more. Just to point out that UNICEF sits in the intergovernmental organisation bubble up there. We’ll talk more about this shortly.

Thank you. Any comments from Ed or Jen on this model?

Yes.

Go on, Ed.

No, you go ahead. Sorry, I’ll comment after. You go.

Just going to speak a little bit to Gavin’s point with third sector. It’s interesting on that diagram, third sector being put with influencing and agenda setting. Obviously, we’re one removed on the interpreting and implementing. We’re dealing with agencies who are interpreting and implementing policy and we’re working with them and their interpretations of what’s going on in policy, and that thing of it not just being the biggest wallets or the loudest voice but, also, that need to stick to why you do what you do. Not regardless of policy but have that kind of healthy thing of doing things for the reasons you do them and not being so directed towards where the direction of policy is going that you lose the essence of your mission.

Thanks, Jen. Ed.

Yes, I think it’s an interesting model and agree with other panellists in terms of that need to get different voices and diversity of opinions at all stages, really; particularly in the developing, drafting understanding what the policy options are. How it is going to affect and impact on different sectors of society? Industry, third-sector, NGOs, and the public understanding, what that does. That’s important at all the stages because when you’re looking at developing policy, you need to factor in how that’s going to work for effective delivery, as well. There’s a question there about delivery of – who delivers? When you’re developing policy aims, who’s going to deliver this? Is this a policy aim that will be delivered through different policy levers, different policy interventions? It could be local government having given responsibilities to deliver something. It could be looking at different market incentives for a more market-driven delivery. It could be around responsibility on industry. That model of drafting, developing and, then, I guess into delivery is quite interesting and very much you need all players and all the stakeholders involved in those discussions at various different stages.

Thanks for that, Ed. Yes, I think what comes through really strongly here, then, is the people element and the importance of all of the different actors and the appropriate stakeholder engagement and, crucially, the inclusion of civil society – which is a glaring omission here – so thank you both Gavin and Al for pointing that out. Okay, so what I’d like to do now is invite our panel to speak a little more about their role in reference to this, if they would like to or, perhaps, in reference to any of the insights gleaned from the pre-work around the perceptions of our participants of working in policy. Just about what their role is like on a day-to-day basis, what the key drivers are, just to demystify it a little for our postdoc participants today. Al, could I invite you to speak first, please?

Yes, of course. I made a note following the previous slide about monotony and burnout. Actually, I think I would probably counter that actually working for a cause-driven organisation is the thing that means that there isn’t monotony and that actually you can counter some of the burnout. My role as Director of Research and Learning at the RSA is very much about building that evidence base to support our mission which is around support a more resilient, rebalanced and regenerative world for people, place and planet. We’re just at the start of that journey, so I think there’s a really interesting thing around policy that we develop for the long-term rather than short-term policy cycles. Particularly with cause-driven organisations, it’s trying to create policy positions that can create that long-term systemic change and that you can see that happening at all levels. Most importantly, I think, for a lot of cause-driven organisations, including the RSA, that is about the impact that that will have improving people’s lives, addressing inequality. I think that whole focus on shifting the system and what that would mean at different levels – what that would mean for organisations and the communities and, also, individuals – was something that really took my journey from academic research into the charity sector; both my current role and my previous role with an organisation called Good Things Foundation, which is a digital inclusion charity. I think there is a lot around having a mission but a mission is not enough. Actually, having really, really clearly defined calls for action, policy positions, are the things that really take, I suppose, a lot of my day-to-day work. It’s built through the work of our entire organisation being able to work participatively with organisations and with communities to evidence the change that they want. I would say, coming back to this first point, that also then does give a huge level of job satisfaction. Because, if you’re in it for the long term, you know the goal that you’re heading towards and that this work that you do on a day-to-day basis makes a contribution to something much more long-term. There are obviously moments where you’re at your limits with it and you’re not seeing that cut-through. I think it is incredibly rewarding when it does happen and when it does cut through.

Thank you, Al. I’d like to invite Gavin to speak in a second. Before I do, in preparation for this session, you and I had a really interesting chat about how you don’t class yourself as working within a policy context necessarily, although your work does seek to influence policy. I guess, the centre of your triangle would be about the cause rather than the policy itself. Do you want to say something about that?

A hundred per cent. I think policy is one route to impact but, actually, there are multiple routes of impact alongside that. I think your diagram, your other diagram captures some of these. Actually, what we want to see as a result is a shift to how practice happens, how services are designed, how support on the ground is available, how education, training, how the commitment to resources… I suppose it goes beyond policy into really trying to think about that kind of whole-systems shift that you want to have as a result; policy being one level and one realm of that but not the whole picture.

Thank you, Al. Gavin, any thoughts or anything to add on to that from your own perspective at UNICEF? I’m sure our participants would be really keen to hear about UNICEF, your role there.

No, no. Thank you. I can’t see everybody. I just had a quick scan, actually, across all the faces and some of you are hiding behind your cameras, so it would be lovely if you – I mean, I know you may choose not to but lovely to be here again. Thank you for the invite. Yes, so first of all, the key role of UNICEF is, I guess, ultimately to advocate to governments, to make sure governments are fulfilling their obligations to the rights of children. Those are set out in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and, also, in the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. That’s the main thrust of where we’re going. When it comes to this model here, in terms of agenda setting, right now, I’m working on establishing a global research agenda for children with disabilities. We’re trying to identify the gaps that would make a big impact for children. The agenda-setting is where we’re actually currently at, at the moment, which will, then, ultimately, inform what we will do, our programmes and the policies which come in between. The policies will determine what we need to do, how we do them, and with whom. For me, this model works very well. I mean, we’ve identified I think that a bigger piece to this model is the principles which come from the research and the policy which is informed by that research and that practice, the three Ps; the principles, policy, practice. I think that’s an important one because we then learn from that practice which is the implementation and, then, we’re monitoring and trying to understand what works. Is it working well? Is it working to a scale that we expect? How can we improve? A big piece of UNICEF’s work has always been in monitoring its programmes and understanding the impact on children on the ground. I think that’s an important part of research. Research could be very mechanical, counting beans, if you like, and looking at how many children have been reached by something. We call that the more information-management and performance-monitoring exercise at the field level. Here at UNICEF’s Office of Research, we are doing a wide range of traditional research that you would have in university settings. We have the qualitative, quantitative, social-science-based research looking at these rights. A key area is to really understand I guess which children are being left behind and can research identify those in the first instance. Then, how can we actually reach them better? For me, this is an important piece to have this model here. UNICEF’s role, yes, across all three of these, so agenda setting, the policy formation – which is for our own policies but, as I mentioned before, we also advocate to governments to have policies. The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is 2005, I think – I may be wrong – but fairly recent, not all governments have ratified that convention, compared to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, for example. So, really pushing for this. We’ll also try to identify, in those cases, how governments are doing to certain indicators. Our research, we create these scorecards which put the United States against England, against Uganda, against Luxembourg, whatever it might be – whether it’s to do with the environment, whether it’s to do with school and education – and that’s a really important area. I think that, then, has perhaps an indirect impact on governments, also, to change their policies. We can’t enforce and we have to be impartial, but we can present objectively our research. We go through this triangle at different levels in our organisations. I’ll leave it there just to give time for either follow-ups or others to add on.

Thanks, Gavin. That’s brilliant. I think we can hopefully look at that in a little more detail in the next section. I’m sure many of the participants would appreciate understanding that and what it looks like on a day-to-day basis. Yes, let’s move on to Jen for now. Any further comments from you, Jen, on your role at the Reader, how that relates to this?

Yes, worth just giving a bit of background about the Reader. I think even if you’ve encountered the Reader, you probably haven’t encountered all of the Reader, so it’s good to have a bit of background on that. The Reader on a mission to bring about a reading revolution. How we do that is our volunteers and staff bring people together to read great stories and poems creating outlets and connections which we call ‘shared reading’. Now, we do this across a number of different sectors, so that point about monotony earlier on I found really interesting because there’s never a boring day at the Reader. We’re working in criminal justice settings. We’re working in mental health inpatient settings. We’re working with dementia and end-of-life care. We’re working with Early Years. We’re working in schools and we’re working in community settings across the UK. As you can imagine, it’s a busy portfolio of providing that evaluation, as Gavin says, to show what works, to understand what works internally so that we can decide where to put our energies so that we can make the most difference. Also, we have a role where our funder is giving us money based on policies. We have to part of their evidence picture. We’ve got to help them create that evidence that then can inform policy moving forwards. For us, there needs to be an awful lot of flexibility with making sure we know what we know to do a good job ourselves but also responding to what’s going on in the wider world, in the eyes of the people who are giving us money to do things. Yes, and to be ahead of the curve, really, because all of you who are working in research will know, it takes a long time to build the evidence base. If policy suddenly has a new direction, we have to be ready for that. We can’t wait until we are told about it. We have to be there with the evidence almost before it’s needed. I’m looking at providing that evidence but working closely with our development team who are keeping an eye on what’s going on in the world of policy, what the trends in funding and grants are, to do all of that. So, very much hearing what Gavin is saying about the importance of being able to tell our funders, and for them to make that bigger case upwards, about what works and what doesn’t.

Thanks, Jen. I wonder if you’d be happy to say a little more on the challenge of being responsive to policy trends whilst not losing your own cause. I know we’ve talked a little about that.

Yes, we’re very lucky. There are some great funders out there who really support charities. We’ve got quite an ambitious attitude towards monitoring and evaluation in our organisation, but we get support to help us with that. We’ve done theory of change work in the past where we’ve had support from external bodies who can give us that assistance that maybe we don’t always have in-house. For us, it’s really important that things go back to our theory of change and why we think that what we do works, and the evidence we’ve already collected. Now, some of you will have seen, for example, Arts Council England awarded their funding last week and there was a lot of chatter in the press about the Levelling Up agenda and what happened to charities in London. You can see how it really affects a charity when decisions are being made. A charity can’t necessarily help if they’re based in London if they’ve not got a London cause going on. For us, it’s about holding fast to our theory of change, seeing the direction the wind is blowing and being aware of that. We know there is ongoing discussion at the moment about social prescribing which we’ve been talking about at the Reader for a number of years now. For us, it’s a real frustration that any charity, on its own, can’t really do the agenda setting, evidence gathering that’s needed that really needs to be working in partnership to do that. We want to be ahead of the curve and it’s very hard to do that as one charity. So, where we can, joining in with bigger organisations like What Works Wellbeing, things like that so that we can build that case for where policy should be heading in the future, rather than where it is now. It’s worth saying, a lot of our funders are actually probably ahead of the policy. Again, they’re doing that stakeholder thing where they’re listening to what’s needed on the ground. Maybe they can move a bit faster than policy; I don’t know. For us, when we’ve tried to, for example, measure things that aren’t part of our theory of change – because that’s an emerging trend – we see that the data doesn’t back it up as strongly as our theory of change which is quite rough. Yes.

Thank you, Jen. You mentioned theory of change quite a few times there and I know that’s a really important thing for many charities. I’m just not sure if our participants are aware of it. Maybe I could ask anyone in the chat to comment if that’s a term they’re familiar with. If not, we’ll come back to it later because I think it’s an important thing to look into. For now, could I invite Ed, finally to comment? What I may do, Ed, unless you particularly feel that you’d like to refer to any of the slides, I know you’ve stopped sharing my screen so we can all see each other. That might work better. What do you think, Ed?

Yes, fine by me.

Okay, great. Okay.

Yes, thanks. I suppose starting just from my day-to-day, what my role is. I head up a policy team within a central government department in the civil service. The role of the civil service is to deliver the government policy of the day. That’s quite an important point, I suppose, in terms of the civil service being a permanent feature for politics and the Government may change in terms of the ruling party and things but the civil service, it delivers policies for the Government that is elected by democracy. One of the aspects is understanding that political ambition. Maybe understanding the politics, the different political ambitions and the different aims the Government want to take. Also, providing objectivity and understanding what the evidence is saying as well. Interesting comments similar to what Jennifer was saying around having the evidence before it’s needed. There’s certainly an element of that, as well, of whilst we’re busy developing policies and implementing policies on specific issues. It’s also trying to make sure that we have that longer-term view, as well, about understanding what the longer-term evidence is saying. I think in terms of the cycle or the diagram you had up, Katie, it was very interesting. We often think about policy developments, implementation and evaluation in a policy-making cycle. I suppose my day-to-day is interacting on various different policy issues at different points of the cycle. My main policy role is in chemicals policy, so understanding how we manage chemical, industrial chemicals, within the UK to meet human health and environmental aims; but, also, needing to understand and balance economic and societal considerations of that. Much of it is in the development policy space at the moment, the political context of having left the EU. Much of political regulatory regime was tied to the EU, so there’s that big-picture politics of what is government doing more strategically. Where does government aim to get to in five/ten years’ time? Interesting, thinking about the theories of change, because we use theories of change quite a lot as well. It’s I suppose two questions, really, we’re often asked. What is government’s position on this? Then, my role is then to communicate or agree that position with ministers and then communicate, ‘This is government’s view on this.’ Also, then, what is government going to do about this problem? There is this issue and what is government going to do? That’s where it’s about influence and influencing organisations, how they influence government policy. I suppose I’m more on the receiving end of that, different organisations saying, ‘Well, this is really important. We think government should do this for this reason and this reason, and this reason.’ Then, part of my role in my team is bringing together all those different considerations, different viewpoints. What does it mean from an evidence perspective? What’s the evidence telling us is really, really critical to that? Also, what are the values driving it and what are the values that are important that are driving this view? How does that align with the political aspect of it? Then, also, then, bringing that together to take to ministers, to advise ministers, to make decisions and then saying, ‘Okay, we’ve looked at this issue. We’ve spoken to a range of stakeholders. We’ve taken on various different viewpoints. We’ve looked at the evidence.’ By evidence, I mean a combination of sciences, physical sciences, any sciences that are needed on a particular issue. Also, economic and social science. I suppose within Defra, we have those three professions of what we call the government, science and engineering profession, economics profession and the social science profession; and bringing those three together in combination with other factors such as legal risks, as well, to provide that advice to government to make government decisions and, then, set government policy on things. Yes, I think very interesting seeing that cycle and the general use of evidence at all different stages is really, really important to make sure that we have agreed aims on what government is trying to achieve. Understand what the different options are, what the different implications of those options are, how we’re going to deliver it. Then, finally through when it’s agreed that this is going to be our policy, move into delivery and, as it’s being delivered, you need to collect data, collect information. Is this policy actually working? Is this policy doing what the government intended it to do? Then, you go around that cycle again. Evidence is really important throughout all of that.

Brilliant, thanks, Ed. Thanks for giving us that government perspective. I should have mentioned, actually, at the beginning of the session that Al, Gavin and Ed are all former postdocs and Jen, herself, also has a lot of experience in the research context. That will be, I think, interesting when we come to explore the relationship between academic and policy-related research. We’ve got about five minutes before we’re going to take a short break. I wondered if any other members of the panel had any further thoughts that they’d like to raise in response to any of the comments so far or, of course, if anyone has any questions… From the participants, if you’d like to put those in the chat. Anyone? Well, I have another question, then, for Ed. We talked a lot about cause-driven organisations earlier. I just wondered the extent to which cause-driven organisations influence policy at Defra. I imagine it would be more environmental causes.

Yes, yes, certainly we work a lot with NGOs, so non-government organisations, charities. Yes, their views and their opinions are very valuable. I suppose understanding – going back to what I was saying – the Government [signal breaks up 0:38:51.9] understanding the important pillar for me is the democracy. I may not always agree with the decisions that are made by my ministers. I may not always agree personally with government policy, but I have a very strong grounding in the fact that they are democratically elected. Any way that we can understand and advise ministers on what are the civil society and, also, NGOs and charities and their role in understanding and are probably close to understanding the issues and the values that are important to people across the country is a very important piece of our work. We definitely work very closely with value-driven organisations.

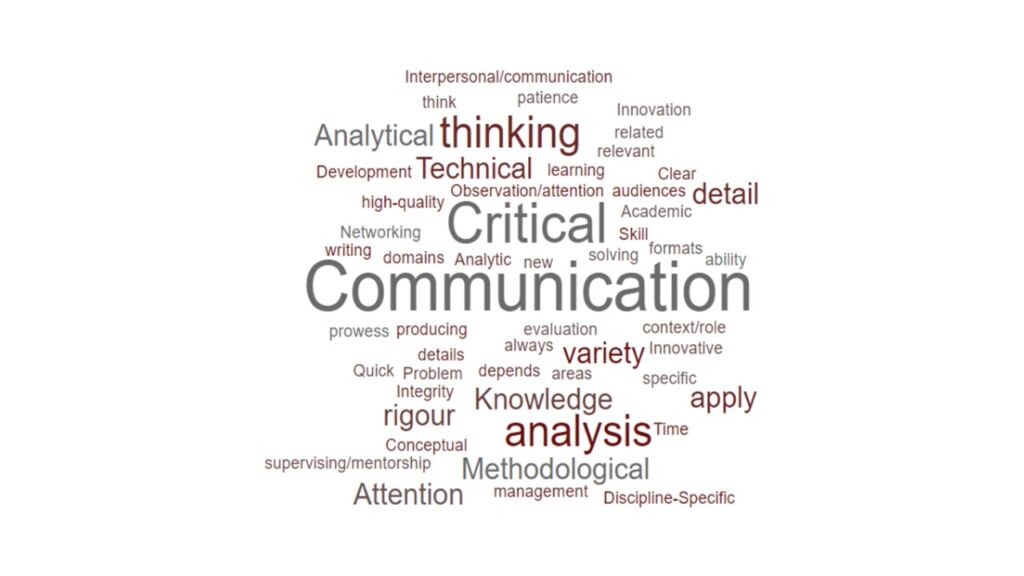

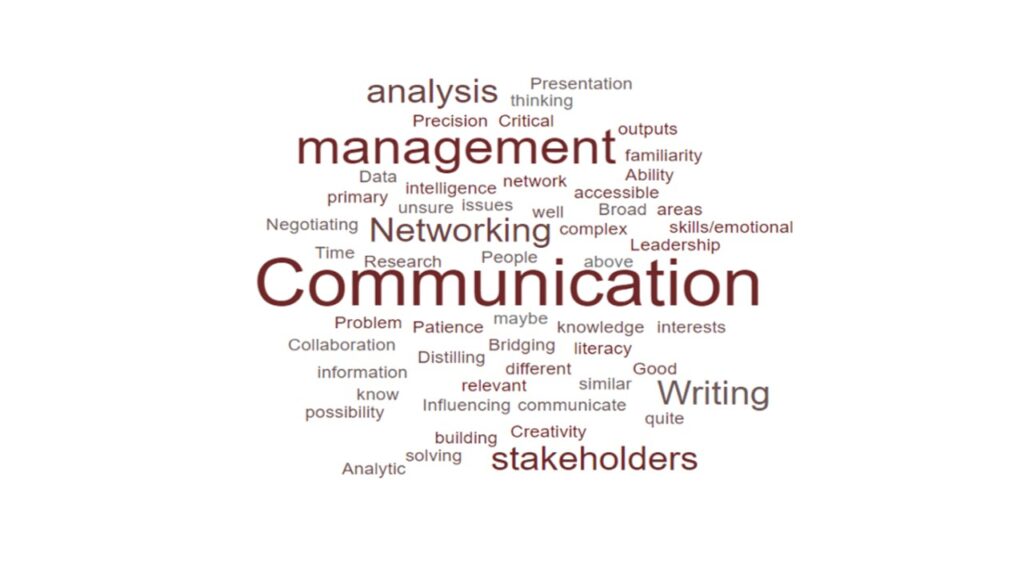

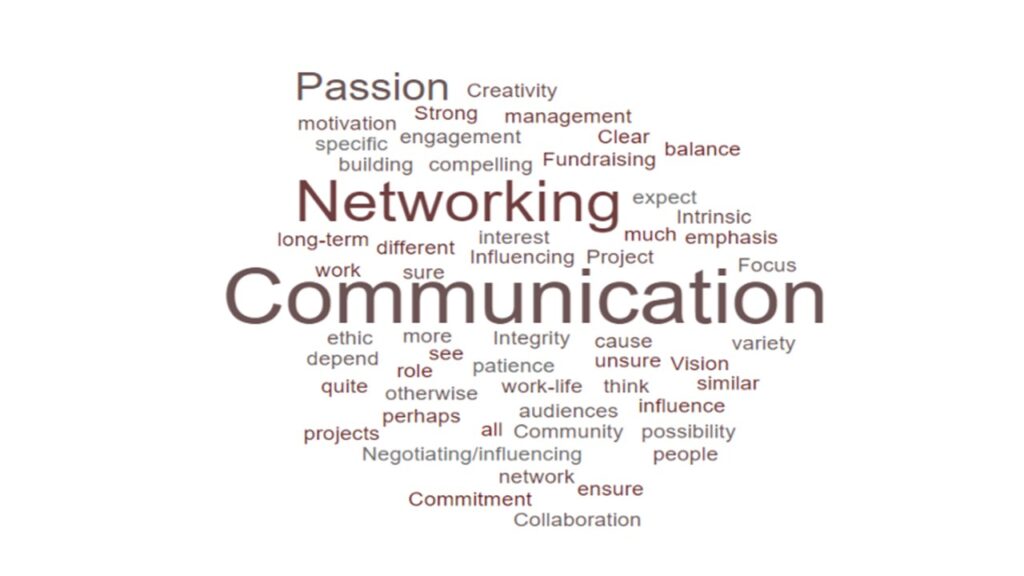

Sorry, I was muted there. We do have another question from the chat around transferrable skills. If it’s okay with you, Lenka, I will pause on that for now because we’ll be picking that up in the next session. Okay, so we’ve got 20 minutes or so now to discuss, in a little more detail, what research means in a policy context, the skills that we might need when working with or doing research in a policy or, indeed, cause-driven context and, perhaps, some of the similarities and differences between the academic and the external non-academic context. Just to stimulate that, as a starter for discussion, I thought I’d share with you a word cloud which just visualises the responses that our participants had – to the questions around their perceptions of – the top three skills required to work in an academic research context, a policy context and a cause-driven context. Just as food for thought, really. Let me share my screen again. Dear me. Okay. Can we all see this? Yes. Great. These are the skills that came through for doing research in an academic context. As we can see, communication front and centre, but a lot of focus on, I guess, the more analytical, technical thinking side. Methodological rigour came through attention to detail, that kind of thing. Then, to contrast that with the policy context, communication, still front and centre. I think with a bit more of a people focus here. Stakeholders is one that stands out. Management, writing, networking, with analysis still an important aspect. Then, finally, just for comparison, cause-driven context responses were these. Again, interesting that communication is the most important across all three. Networking and passion coming through really strongly here with a lot more, I think, of a people focus. Perhaps that’s where we can start. I’d like to invite any panel members to share their thoughts on that and draw on their own experience and respond as to whether they agree with this broad trend or have any other thoughts to share. I’m going…

I’m happy to go first if you want a volunteer.

I was going to pick on you! Yes, that sounds great. Thanks, Gavin.

It’s interesting. I reflected on these word clouds, obviously, beforehand because you’d shared them so thank you for that. I thought it was interesting that communication comes up and I think that’s critical in life, in marriage, in everything. It’s an important thing to have. Also, what struck me is that I think that it depends also on… If we just take a university and a research context, it really depends also on that. If you’ve got a very blue-skies thinking, very academic university, compared to… I was at Cranfield University and Cranfield University is a very world problem-solving type of area. I think there’s as much variation across universities as there is, perhaps, in these different areas. I think what struck me, we’ve got skills plus, then, what we… In UNICEF, we’d differentiate between skills than core competencies. These speak to a bit of both with communication as a competence as well as a skill, I guess, but it’s one of the things that we have. I would say, certainly in my journey, which I’ll talk to later of course, but I think that the communication, the drive for results, I’m not necessarily seeing that up there. It might be there. Respect for others, working in teams – even if you’re an introvert – those things are quite critical and managing the self, managing yourself, I think are quite important. I would say the pressures come in different directions but all those things will stand you in good stead to work, whether it’s in the policy context, whatever that means, outside of the university system. My reflection, really, was there’s probably as much variation within as there is across these different areas. That’s my first thought. I’ll just leave it there in case others want to come in. I can speak more to this in a moment.

Thanks, Gavin. I just… Yes, lots of questions and thoughts but I’ll leave it to the panel first. Anyone from the panel like to comment on these? Yes.

Yes.

Sorry. Ed, you go.

Sorry. I think just adding to what Gavin says, agree. I think within a policy context or a policy organisation, there are different roles and different skills within that. I started in Defra in a very technical specialist role and I’ve moved through from technical specialist when the skills maybe are slightly more aligned to what you would need in a research/academic context. Then, I’ve moved through various different roles and I’m now in a more pure policy position role where the skillset changes. I think, as well as the different skills, there are opportunities for that even within an organisation and a variety of roles within the same organisation, where you need a different blend of skills and competencies and experience.

Yes, that’s interesting. Yes, there’s diversity within the two contexts and it doesn’t necessarily make sense to compare the two. Would you agree with that, Al?

Well, no, I was going to say, I think there is just huge synergies across all of these. I think the thing that I was struck by that was missing was just that focus on being impact-driven. I don’t know whether you’d describe it as competency or a perspective that I think could cross all of these different ways in which research and policy can be developed within an academic or a public-sector or a third-sector context. I think there’s a really interesting thing about research is pretty, pretty broad. Even within an academic context, you can have research that spans everything from highly technical data-driven research to truly ethnographic and participatory. All of those things have a role to play in making a really, really strong evidence case for the kind of change that you want to see in the world through policy. I think there’s something about being able to recognise multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary practice skills that you might have. Because, actually, being able to say, ‘Evidence doesn’t just come in one form,’ and that actually the best kind of policy is made by being able to draw on a multitude of different kinds of evidence and see where the commonalities and synergies are that give you a really clear position… I suppose all of that feeds through to the idea that, actually, then you can communicate and will communicate with credibility and with impact.

Thank you, Al. Jen, I can see you’re getting ready to speak.

Yes, yes, just to echo, really, what all the panel are saying. I was particularly drawn to, communication aside, what’s going on in the top left of all these word clouds and that analytical thinking here versus on the next slide to do with passion. I really think you need all of that in probably every role. You can very easily lose track of where you’re trying to get to if you don’t have those analytic, strategic thinkers holding to you account. As we would say at the Reader, ‘Bringing you back to the text,’ and saying, ‘Is this the best way to do it?’ I wouldn’t make clear-cut distinctions, really. Here, at the Reader, and I have to mention in lots of charities we want to get people to bring their whole selves to work and we want that difference. If we all think in the same way and we all have the same dynamic, we’re not going to be catering to all of the needs of the people we’re trying to reach. So having that balance of people who will apply one lens to something and people who will apply another is a real asset. We want diversity in our workforces because we want all those different minds in the mix, just like all those different kinds of research methodologies and approaches.

Thanks, Jen. Interesting that there’s consensus on that. I suppose my question would be, for the postdocs here, if we’re saying that there’s not really a difference, what is it that…? Are we saying that postdocs will not need to develop new mindsets/approaches if they were to move beyond academia?

Yes, I think the interesting thing is that you’re held to account for the influence that you have when you’re in policy roles outside of academia. A lot of the way in which it comes back to the evaluation point and the impact measurement point, part of it is that if you make this really, really well-evidenced case and are held to account on the impact or the outcomes that that achieves, that is I suppose a different way that your role and your skill-set… Sorry, your role might require a different skill-set because part of that is how you take that out into the real world beyond your organisation so that it doesn’t just stay as a kind of paper. It’s living and breathing. I would say there is something around those kinds of – and it goes beyond communication. I think there is an influencing part. It’s probably just in there at the bottom, negotiating and influencing, but I would bring that out much stronger.

Okay, yes. Thanks, Al. Gavin.

Yes, I was just going to say that, in many ways, it really does speak to the point that, as you progress through your career, you don’t necessarily have to stay in the narrow corridors of the research building that you’re in now, or even on the topic that you’re in now. As you progress, as Ed was saying, you’re going to take on more responsibilities. You could do that within the university context. If you then want to become a group leader, you’re going to have to take responsibility for understanding the strategy that you’re going to take and for fundraising; and for bringing in all sorts of things that you didn’t do when you first started. You could also step right and go up into something which is perhaps more in one of these other areas that we’re representing and do the same thing. I think you referred to it as a monkey bar and we’re going to talk about this, or whatever it was you said…

Yes.

That sort of thing is quite manageable. I think what this tells you is that it’s absolutely possible to do what you want to do. Whatever you decide you want to do as a career, you can do it because the skills are so critically similar.

Thanks, Gavin, for that really positive reassuring message. You’ve actually led us really nicely on to the final section which is all about charting your career in policy or, indeed, in any other context. Just to provide a little bit of context to what Gavin was saying that one of the things that we talk about with Prosper is this idea of multiple routes to success – and broadening postdoc horizons beyond a single track to success – which would be the academic career pathway which, of course, is fantastic for many people. Many people will continue to pursue that which is great. There are many other routes, varied routes, to career satisfaction, to making an impact, to a fulfilling career. One of the metaphors that’s used a lot for that, when describing that kind of thing, is moving beyond this idea of the career as a ladder, where you will always make subsequent steps up in the same field, to this rather American idea of a jungle gym which – just ignore the language, because it is quite irritating… Essentially, this idea that you may sometimes take a sideward step to broaden your experience. You have the much broader perspective. You may take an opportunity over there rather than up here. I think it was Sheryl Sandberg who popularised the phrase so, yes, very American. With that in mind, I know that everyone here, and Gavin I would say in particular has had a really interesting career trajectory, so I’d like to invite you first, Gavin, to talk a little about what made you move beyond academia, the things that you learnt along the way? Anything you’d be happy to share?

Yes, I guess, I started off at Cranfield University. I did my master’s degree in satellite imaging. I was really interested in earth sciences and the environment. That took me into teaching on the master’s course that I’d just finished and I basically stayed in that university for 16 years. I was going up the ladder, the single ladder, I didn’t step aside for 16 years. As I was developing through that, I was taking on responsibilities and I left in 2010, 2009, as a Senior Research Fellow, with a very big project looking at climate impacts on extreme weather in the UK. We had 18 universities that I was managing, to take forward. My director of the institute told me I was crazy. I think he actually said I was ‘Brave’, the word he used, for leaving at the point that I left service. This was a euphemistic, telling me I was crazy. As I was progressing through that I realised, first of all, I’d moved through very different themes. The thing that drove me most, I was interested in the purpose of the research and not necessarily the research itself. I was thinking more strategic, and thinking of taking on more leadership angles. That’s what I wanted to do. Then, I took a very wild swing. In passing, I decided to record an album and I then found myself performing in front of 20,000 people in festivals, the music I’ve recorded, which was me taking a step aside to think about, do I want to continue doing that research. I really didn’t know what I would do next. A few life events happened and I decided just to pursue something I’d always wanted to do, tick something off on the bucket list. I wasn’t long into that when the earthquake happened in Haiti and some folks, I did my master’s degree with, rung me up and they were working in that response and they said that they needed someone with some skills. So, coming back to the skills, so my research skills, were very much a lot of databases, geographic mapping, satellite imaging, a lot of stuff which was very transferrable and useful; to looking at emergency contexts to keep track of people that had been affected by the earthquake and where they were mapping spontaneous camps and, then, also looking at how many people needed water, who was accessing water and sanitation, etc. I saw it as an opportunity. I then jumped into that. That was my shift across. As I was doing this, as I was thinking about the move, I did think about my skills. I was thinking, what can I offer? I remember thinking, initially, I have nothing to offer. There is nothing I can do in this role, surely, but I went into it and I suddenly found that it was what I’d been waiting for. That was my career goal, so I went suddenly clear and I wanted to stay in that area, so I did. I then worked in that role – and I’ll finish in a minute, just one more minute.

No rush.

I worked in Haiti. I was living in a tent, sleeping in a small tent in the airport and I was working with colleagues in another tent during the day. For lunch, we’d go to another tent to eat. I won’t make the joke. It was intense. I have just made that joke. It was just a very interesting career and it compelled me because it was very motivating to see the impact of the work immediately. Then, I was offered a job in Geneva to head up a whole new movement related to information management, so building on those skills, those database skills. I moved to Geneva and I worked there for seven years. Then, an opportunity came up to start focussing back on the research, at the Office of Research, Innocenti. What gave me the confidence to make these moves in this last – that’s been 12, nearly 13 years now since I left the academic career. My approach to thinking things more strategically, trying to understand goals, theories of change that were mentioned before and that’s a critical part of the work. Yes, that’s where it’s got me here. Each time, I did take stock of what is it that I do that’s transferrable. I think it’s very important to identify those transferable skills. That’s it. That’s my strange journey to where I am now if that’s helpful.

I’m sure it is, Gavin. Thank you so much for sharing that and also for reinforcing something which I think we try to emphasise in Prosper, as well, which is that recognition of the value, first of all, of those transferrable skills. I think, as I know, our participants may disagree, but I think sometimes in academia, the focus is very much on research output and not necessarily the skills that have enabled you to get to those outputs. I think a lot of postdocs have a fantastic skill-set but don’t necessarily reflect on it as much as you have. I think that’s a good lesson for everyone. Any comments or questions for Gavin from the floor? No. Okay! Fair enough. I just have so many. That’s why I’m surprised. Anyway, let’s move on. Jen, would you like to speak next? I know your background is really interesting, as well, from contemporary art to data.

Yes, yes. I’ll try and answer Lorna’s question too. I’ve seen that, Lorna, so I’ll cover it when I’m talking about it. Yes, I did six years at art school. I was going to be an artist! This was back in the days where you really weren’t encouraged to have a job while you were studying. I had Arts and Humanities Research Council funding to do a two-year master’s at Goldsmiths, where you weren’t allowed to do over a certain number of hours of work in a week. I graduated into a recession with a lot of art degrees and no real work experience. If anyone here feels like they’re in that boat, they’ve been in the academic bubble and not made it out yet, I really feel for you, especially with what’s happening now. I always thought I was going to be a Fine Art lecturer, that was where my heart lay. I was like, ‘That’s what I’m going to do.’ I’ve fallen out of love with academia. I needed a break from it. I had a hard time finding a first job. I really had to revise the was going to be for me to begin with. I thought, it’s just going to be something that gives me an experience of being in the world of work, of getting out of this very small bubble, of seeing the same people in all the same symposia. You see the same familiar faces, to every presentation you go to, and do something a bit different. I worked for a year in a boarding school. They paid for your accommodation and food and not much else. That was a full-time experience. I came out of that going, ‘I could do admin. I’ll just do some admin and find my feet in the world a little bit.’ I wanted to do it in a cause-driven organisation that had my values. I found the Reader. It was in a very affordable part of the country which was a plus and started in a very generic office role. We had introduced a computer system that people were getting to grips with and, in my role, I was supporting a lot of staff in using that. Through that, I found this talent for pulling off the data, inferring things from it and looking at what it was telling us. That coincided with some austerity cuts about eight/nine years ago. The Monitoring and Evaluation Team was born and I fell into that. It wasn’t a pre-existing role that existed and there was a vacancy; it was created and I moved into it. During my time – going to Lorna’s question – I’ve had amazing opportunities to work with organisations who want to support charities, to build that evidence base, both within their organisation and across. I did a brilliant project with Sutton Trust and Esmée Fairburn which was working with University of Oxford. It was partly to get charities better at evidencing their impact. It was longitudinal research over a long time, feasibility studies, and it was part of the Parental Engagement Network. There was an overall goal to it which wasn’t just my charity’s goals. There were a number of charities working together to work things out as a group. That was brilliant. I was part of a research project that the University of Liverpool were working on with other universities looking at Early Years cognitive development. That was a really interesting example. I know Katie was saying about, ‘Are there any differences?’ I would say one thing that I’ve learnt from working alongside university researchers is it’s that world of the ideal research setup versus what you can do on the ground with a real-world situation. Especially when a brand identity is involved too, I think. Giving out huge information sheets about what you’re about to do when you’re trying to be accessible, friendly, no pressure, there’s a real pragmatic challenge there that you’ve got to overcome about how to balance that. Also, the experience that our on-the-ground project team was having and saying, ‘I know you want to deliver every week of the term but if you go into a secondary school, they’ll tell you they don’t want you until October.’ So, all of that stuff.

Thanks.

Sorry, do you want me to…?

Yes, if you wouldn’t mind because we’re running short of time. I do want to give everyone a chance to speak. Okay, so I can see we’ve got, after my rather passive-aggressive pressure, some questions in the chat. I can see that Lenka has asked a question about the experience that Gavin drew on for his role which he’s responded to. Analytical thinking, strategic thinking and also had specific technical skills around GIS and programming. I’d like to invite Al and Ed to speak for five minutes or so about their own career trajectories. If you could kindly bear in mind some of the questions from the chat around the transferable skills and what you took from your research into the really exciting careers that you’ve had since moving beyond academia, that would be great. Al, would you like to go first?

Sure, I was just typing and I’m very slow at typing so it’s probably easier to speak. Yes, my academic career started in landscape architecture. I had always imagined that I would end up being a design professional. That carried me through into my master’s and, during my master’s, I had a bit of a wake-up call where actually being a person who professionally designs for other people’s experiences, and not centring on really understanding the experience that they want – therefore, using my design skills to help fulfil that ambition that they wanted – just shifted my whole view. It was something that, at the time, participatory design within architecture/urban design/landscape design wasn’t really central. That led me to develop a PhD with the PSR team – where we were working with people with learning disabilities – to actually show that huge numbers of people who never have a voice on the design of particularly public spaces, that we could reverse that quite significantly. I think through that journey and then into my subsequent postdocs, I worked with schools in very deprived areas, and particularly Early Years and primary school children about the design of their own immediate environments and community settings; alongside continuing to work with communities of people, of disabled people, across the UK. There was something that that focus on participation and actually how you could really focus on developing research project design and management skills; where from the outset, you designed to ensure that those experiences were the things that could drive change and be also a case for, I suppose redressing the balance around what robust evidence was. That was really critical so I think there was a bit also there where it focusses back on the transferrable skills around communication because it was very much about making the case for doing things differently. Then, being able to demonstrate the worth and the impact of that with different stakeholders. That led me to think that actually, I was interested in public spaces and I was interested in green spaces but, actually, that defining commitment to participation, it was interesting what other spaces it wasn’t participating and not happening in. I think one of the things with a lot of research is that you’re just interested. You just want to know why something is the way it is or why it isn’t happening. I think the fact that digital was starting to be the space that, actually, we were all spending a lot more time in but it was very – it was designed not necessarily with a broad understanding of user experience from the perspective of people who might have different needs. That took me into a totally different area of digital inclusion and digital skills. Subsequently, my journey has taken me to the RSA where I’m just really interested in understanding experiences, where we’re looking at a more regenerative future. I think there’s something about I could have stayed and tried to just see research as being subject-specific. What drove me was just the questions that we weren’t asking at the time and the people’s voices who weren’t being heard on things. I think coming back to Jen’s point of values, I knew there was something there. If I could see an area where that kind of change, or a change needed to be made, it was being values-driven and applying different research methodologies and a commitment to participation to change. Where I am in five years, may be very different from where I am now because I think I continue to be inspired and intrigued where we’re seeing inequalities happening and the change that’s happening to our world around climate. The impact that that’s having on communities is something that I think probably will be where I head next. I was going to say that I think that – whether it’s a jungle gym analogy or whether there’s something else going on – actually, I think at the heart of research, it’s about asking questions. If you have a really good focus on, ‘What’s the question that’s not been answered at the moment?’ – or, ‘What is the question we should be asking?’ – then that’s something that you can carry across; a very, very transferrable skill.

Al, thank you. That’s, I think, a really good piece of advice and something that we can all reflect on. Really interesting how everybody has shared something about finding their purpose or suddenly having clarity of purpose. Interesting to hear if that’s relatable for anyone or maybe you’d like to reflect on it. Ed, last but not least, what would you like to share about your career journey?

Yes, interesting, on that last point you were saying about finding your purpose. I was looking over some notes of when I’ve done careers talks or talks on careers development to people within Defra, and I often start with a phrase saying, ‘Careers development and thinking about career planning is for everyone including those not interested in promotion or for those that are happy in their existing role,’ and things. Then, I was reflecting on that in terms of my journey postdoc. I reached a point. My background is in chemistry and, after PhD, did a couple of postdocs and generally moving from a very blue-sky – into more industrial-focussed research. I was pretty happy doing that, to be honest. Then, the organisation I was working for, my contract was ending and I didn’t have an opportunity to do that. Although I often start these days in terms of careers talks thinking about, even if you’re happy in your role and happy in your job… Oh, sorry, I don’t know what happened there.

The last thing I heard was, ‘Even if you’re happy in your job.’ Can you hear me?

There was a glitch. Back. Right. Am I back?

I think you’re back, yes. Can you hear me?

Is that okay? Can you hear me all right?

Yes, I can hear you. Yes.

Sorry. Where did I get…?

The last thing I heard…

…to on… Where did I cut out?

Yes. See, I’m not sure if it’s you or me with the poor connection but the last thing I heard was, ‘Even if you are happy in your job, career development is important.’

Yes, I was saying that that’s normally how I start careers talks when I do them in Defra. Actually, in my personal journey, I was pretty happy in my role and pretty happy in my job but it was on a short-term contract that was coming to an end. I really had to evaluate and think about, well, what is it about this career path that I think makes me happy and think is valuable? Are there other ways that I can still get that career satisfaction, career fulfilment? For me, it partly came down to wanting to have impact. Impact is a word that’s come up quite a lot there; using my scientific skills and experience to have impact. I was thinking about it through an impact in industry, developing new products and innovation kind of thing. I actually started to look at the civil service and thinking about impact in using those research and scientific knowledge and skills in a different context to have impact. The other aspect, as well, was around the values of public service and wanting to have impact for public good. That really attracted me to move into the civil service. I moved into the civil service in Defra. I’ve been in Defra my whole civil-service career for nearly five and a half/six years now. I’ve moved in different roles but I think, in the first one, it was a very technically-focussed role. My scientific knowledge in my area of specialism was important to deliver that role. Then, there were opportunities for promotion which moved me away from my scientific specialism but still using scientific skills. So, project management, how to run a research project. What are the different stages? Where do you need to understand the risks for delivery? Research is unexpected twists and turns, how to deal with them. Then, as I moved up through responsibility, not just about my personal effectiveness. I moved from being a postdoc of like, right, I’ve got my project plan, here’s what I’m going to do for six months. I’m going to do this experiment and this experiment, analyse these results. Of course, that relies on working with others, as well, but certainly through working, moving up in seniority, managing programmes rather than projects, leadership has become really important as a skill. I suppose in terms of skill, it’s not just delivery of my personal effectiveness to delivery but how you work through others and how you get others to deliver on things. So, those skills around communication, management, people management, being able to understand what drives other people and being able to use that and understand what they’re trying to deliver – and agree common goals and deliver that – has become more and more important. So, skills around leadership, delivering, effectiveness of delivery, beyond my personal role but, actually, allowing other people to deliver really, really good work as well. Then, I suppose I’ve moved more and more away from my skills of scientist, in terms of my technical knowledge, but still moving and still maintaining some of those skills. I think particularly Al was saying around analytical thinking and asking questions is a really key skill. There is also knowledge that you have as a postdoc and having worked in that system that is important as well. Transferrable skills are one thing but, also, understanding that you work in a system where you understand what that science and research system looks like, what drives academics, what drives the science and research. When I’m working now, I’m trying to work with academics to get advice, latest thinking, have a better understanding of what drives them and that improves the working relationship there as well. As well as transferrable skills, there is knowledge and experience that are really valuable as well. I’ll stop there. Thanks.

Thanks, Ed. Thanks, everybody. Some really key things coming through there which we haven’t really touched upon but, of course, leadership skills are really vital, aren’t they? Especially as you progress in your career. We’ve talked about project management skills throughout Prosper, as well, or at least an awareness of project-management principles and the importance of that. It’s such a fast-changing economy/society. We’ve only got a few minutes left. All that remains, really, is for me to really warmly thank all of the panel for their generosity of contribution. Thank you to all of the participants for completing the pre-work in your engagement today. I’d like to ask you – and please feel free to ignore the request but I’d like to ask everybody in the chat – just to share one key takeaway from today. If there’s anything the panel would like to share, maybe a final piece of advice to postdocs considering moving beyond academia, either verbally or in the chat, please speak up now. I’m putting you under pressure here. Gavin, did you just unmute?

I did. I’m not sure if it’s Plato or Socrates, it could have been neither of those.

They’re essentially the same person.

Basically, there is this journey in life that when you’re doing your journey, you’re looking at the next step, it seems quite random and difficult and challenging. Then, when you look back on it all, it makes complete sense. I think it makes complete sense because you have, basically, taken all the things that you’re good at and you’ve moved to, perhaps, the next thing because you’re good at it and it attracts you, or it’s a cause and it’s something that you want to know answers to, as Al said. I think it’s an interesting perspective. The jungle gym sounds a bit random to me. Perhaps, I don’t think it is quite like jumping from one thing to the next and not quite looking and leaping. I think it does make perfect sense when you look back.

Thank you, Gavin. Okay, well, if there are no further comments, I would just like to wish everybody a lovely evening and thanks very much.

[END OF TRANSCRIPT]

Policy landscape

When you consider working in policy, what types of organisations and sectors come to mind?

Policy is a very broad area, not confined to a single sector. Policy roles can be found across a range of organisations.

Examples include:

- government

- NGOs and charities

- IGOs

- the private sector

Duties when working in policy

Policy involves many different areas and duties. These include:

- Drafting, developing and disseminating policy

This is often considered as ‘policy-making’ and is typically the work of national and local government as well as intergovernmental organisations. In the UK, the civil service plays a key role in gathering evidence to influence policy. Increasingly, the private sector also forms part of this picture. Organisations such as Kantar Public provide governments and other public and private sector bodies with research and data to assist with policy making, in the UK and beyond. Other organisations, such as Oxford Policy Management, have a more global policy focus.

- Interpreting and implementing policy

All manner of organisations stand to be influenced by government policy. Some organisations have a policy function which is tasked with keeping abreast of government policy as it relates to their cause or business interest. This can be the case in the third sector – where government policy will likely shape the funding landscape and define national priorities – as well as the private sector, where national policy will influence business planning.

- Influencing policy or ‘agenda setting’

This comprises efforts to shape policy, be that through the publication of research, stakeholder engagement or lobbying.

For example, IGOs such as the WHO and UNICEF synthesise evidence and develop policies with a view to influencing national government policies in relation to their respective causes (in this case, global health and children’s welfare).

A model for the policy landscape

Taking the different types of organisations and areas of policy into account, we developed this model of the policy environment.

In conversation with the employer partners, the model was considered a useful and accurate portrayal of how policy works on a systemic level.

But the partners wanted to also emphasise the important role of civil society in policy making. These are the individuals and communities who are affected by policy and for whom policy is made.

Working in policy

The employer partners were asked to comment on how the policy landscape model relates to the day-to-day realities of their roles. As the employers were from a diverse background, we had the perspective of central government, an IGO and cause-driven organisations.

- National government: the UK civil service

Ed Latter, who works within the UK Civil Service in the Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) gave us an insight into what was involved in working in a policy team for central government. He outlined that the role of the civil service is to deliver policies for the elected government. This involves an appreciation of the political ambitions of the government balanced with an objective understanding of what the evidence is saying in relation to a particular issue.

Ed’s role lies largely in the ‘policy-making’ area of our model. His team structure their work around a cycle of policy: development, implementation and evaluation. The day-to-day role involves interacting on different policy issues at different points in this cycle.

To do this, Ed needs to understand the ‘big picture politics’ of what the government wants to achieve and marry this with relevant economic, environmental and social considerations.

He brings together different viewpoints, interests and evidence. He seeks to understand the values that drive these, how they align with the political agenda and synthesises this in order to advise ministers and assist their decision making.

Use of evidence is critical at every stage. Evidence from a range of fields is deemed important, from science and engineering to economics and social science.

- IGO: UNICEF and the World Health Organisation

Gavin Wood gave an insight into working at UNICEF. UNICEF is an IGO whose key purpose is to advocate to governments and to ensure that they are meeting their obligations to the rights of children.

These rights are set out in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities both of which provide an important framework for all of Gavin’s work.

Gavin sees UNICEF’s role as touching all aspects of the policy landscape model, but suggests it aligns largely with the policy influencing/agenda setting section. Gavin is currently establishing a global research agenda for children with disabilities. He’s setting an agenda which will ultimately inform a research programme which, in turn, should foster national policies that protect and promote children’s rights.

For Gavin, a consideration of the three P’s of ‘Principles, Policy and Practice’ is important. A large part of UNICEF’s work has always been in monitoring practice ‘on the ground’, assessing the quantitative performance of programmes but also carrying out both quantitative and qualitative research into children’s rights. This includes looking into which children are being left behind, and how research might help them.

UNICEF present their research neutrally and cannot enforce anything upon governments. However, they produce data and ‘score cards’ on all countries, assessing their progress as regards to meeting their obligations under the conventions. As well as providing useful data and sources for comparison, this has indirect impacts on government policy.

To take another example, the World Health Organisation, another IGO and also a UN Agency, like UNICEF, is tasked with promoting global health. One of their core functions is the development of global guidelines containing recommendations for clinical practice or public health policy. These typically relate to diseases such as Malaria, HIV or Coronavirus and are committed to high methodological quality and evidence-based decision making.

Governments are not required to adopt the recommendations of the WHO guidelines. Indeed, many countries develop and publish their own national treatment guidelines, which may be produced by clinical societies as well as governments. Yet the existence of the global guidelines is important. Many countries who do not adopt them may feel obliged to explain their departure from them, with reference to the specific realities of the populations they serve.

IGOs form an important part of the international policy picture. At once somewhat distant from the day-to-day reality of national government, yet vital in setting the agenda and holding nations to account.

- Cause-driven organisations: The RSA and The Reader

For those people and organisations driven by a social mission, policy plays an important role in how they promote and advance their cause.

Al Mathers is responsible for building the evidence base to support the social mission of the RSA. She points out that cause-driven organisations are recognising that policy should be developed for the long-term to drive systemic change. This means taking a more strategic approach to building an evidence base rather than working with short term policy cycles. For Al, it also means ‘being the change you want to see’ by enacting participatory methods of research and service design.

Jen Jarman, Head of Monitoring and Evaluation at national charity the Reader, discussed how her role has a dual purpose. Firstly, evaluation is carried out for the organisation to develop its internal understanding of its practice: of what works best, what is most impactful, in order that they continuously improve practice and prioritise resources effectively. Concurrently, funders who support the work of the Reader may have their own policy priorities, so the evaluation work of many charities must also speak to the funder.

Jen highlights that this can be a point of tension for many charities and requires flexibility regarding what they internally know is working well, and the broader external perspective. Jen highlights how having an organisational theory of change can help guide and ground a charity when working with this tension.

Both Jen and Al agreed that working in a cause-driven organisation and the knowledge that one’s day-to-day work contributes in the long term can bring a huge level of job satisfaction.

If you would like to hear more detail from each employer about their role, watch here.

Skills needed when working in policy

Ahead of the workshop, the postdoc audience was asked to provide their thoughts on the top three skills needed to work in an academic research context, a policy context and a cause-driven context. Their answers are depicted in the word clouds below. How do your perceptions of these areas compare?

The employer partners were then invited to discuss these word clouds and give their views on the skills required to work in these areas.

A number of additional skills and competencies were mentioned in the discussion. These include being impact-driven. In policy, you are held accountable for the change that you make. This was contrasted to academia, where your research output may be prioritised.

Negotiation and influencing skills are vital and require a higher level of communication. You need to be able to influence others when in a policy role beyond academia.

The best policy is made from an ability to synthesise evidence from a range of disciplines and approaches. An appreciation of multiple disciplines and interdisciplinarity is important. This is perhaps something you are familiar with as a postdoc.

Respect for others, working in teams and managing yourself were also considered vital competencies.

It was agreed that many of the most in-demand skills are transferable across academia, policy and cause-driven work. There are several roles within policy organisations. Some more technical specialist and some requiring synthesis of technical and non-technical elements. There are opportunities for a diverse range of people, no single desirable skillset and people can have different strengths.

Suggested task

Login or register to add these tasks to your personal development plan.

“As you progress through your career, you don’t necessarily have to stay in the narrow corridors of the research building that you’re in now, or even the topic that you’re in now. Whatever you decide you want to do as a career, you can do it as the skills are so critically similar”

Gavin Wood, UNICEF

Policy career pathways

The employer partners then shared their personal journeys in policy to date. Some key themes emerged. There are no ready-made routes to career satisfaction and professional development in policy. You need to have a sense of purpose and knowledge of your motivations. An ability to identify and understand the value of your transferable skills is essential. Listen to each of the employer partners share their stories below.

Gavin Wood, UNICEF

Gavin shares his inspiring journey from senior research fellow, to musician, to disaster relief work in Haiti, to UNICEF.

“I thought, I have nothing to offer. There is nothing I can offer in this role, but I went into it and suddenly found that it was what I was waiting for. It was very motivating to see the impact of the work immediately.”

Al Mathers, The RSA

Hear Al share her passion for participatory practice that has driven her career.